To the page “Scientific works”

Dr. Sergey V. Zagraevsky

Typological forming and basic classification

of Ancient Russian church architecture

Published in Russian: Заграевский С.В. Типологическое формирование и базовая классификация древнерусского церковного зодчества. Saarbrücken, 2015. ISBN 978-3-659-80841-8

Annotation

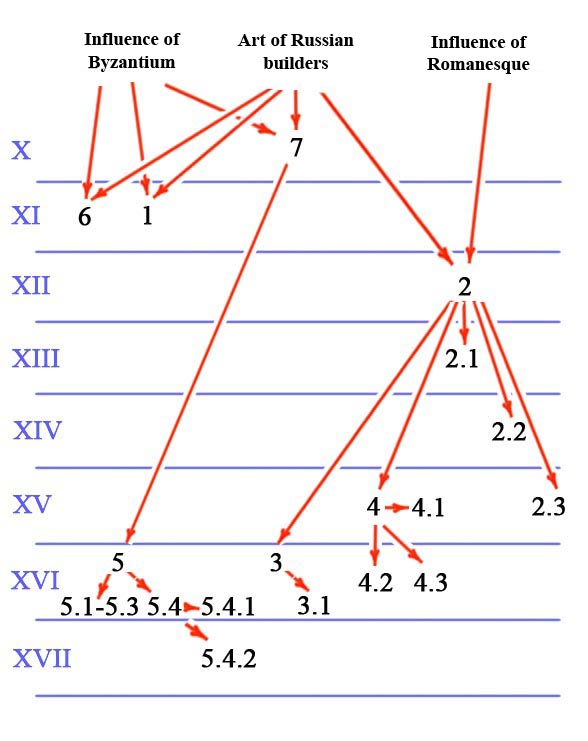

The offered scientific work covers a wide range of issues of forming of the basic types of the ancient temples of the XI-XVII centuries. The complete picture of typological genesis of Ancient Russian architecture from its Byzantine and Romanesque origins to exceptional diversity of the XVI and XVII centuries is issued. A number of significant methodological problems of research of specifics and symbolics of church architecture is considered. Classification of church architecture of Ancient Russia on the base of the typological characteristics is provided. The work is based on the latest architectural, archaeological and documental data.

The book is recommended for the professionals (historians, art historians, architects, restorers and others) and to a wide circle of readers interested in history of Ancient Russian architecture.

Scientific editor – S.Ju. Popov.

Editor – O.V. Ozolina.

Saarbrücken, 2015.

ISBN 978-3-659-80841-8

Introduction

Classification of forms and elements of Old Russian church architecture is an issue with which history of architecture deals not for the first century. Describing the buildings intended for Christian liturgy (we will generally call them the temples), researchers characterize them by a number of features. Obviously or "by default" the following features are present at the description of each temple:

– basic typological features – the plan and the ceiling. Describing the plan type, we usually speak about characteristics of the main volume of the temple (quadrangle, octagon, rotunda and so forth) and quantity of supports (pillars, columns). Describing the ceiling type, we speak about various vaults systems (cupolas, cylindrical arches, hipped roofs, cross-like ceilings, closed ceilings and so forth);

– secondary typological features – altar apses, domes (which can include not only cupolas, but superstructures above them), choruses, galleries, antechurches, refectories, ladder towers, basements, terminations of the facades (arched gables, trefoils, double-gable roofs and so forth), side-altars (as external, and on choruses, in apses, in basements and so forth), existence of a belfry (temples "under bells")2 and so forth;

– construction materials (plinthite, natural stone, shaped brick, wood and so forth);

– constructive and technological features (existence and arrangement of lesenes, outlines of the arches, sails, tromps, existence of external and internal bonds and so forth);

– stylistic features (architectural figurativeity, proportions, forms of portals, arches, windows, domes, features of decorations and so forth).

All these features are mentioned by researchers in connection with each temple, are used as the basis for datings, are grouped by regions, eras, global styles, etc. Definitions of these features, questions of their genesis and time frames are a studied subject repeatedly.

But none of researchers offered a general classification based not on a formal feature set, but on an integral picture of typological forming of Old Russian church architecture of the XI-XVII centuries.

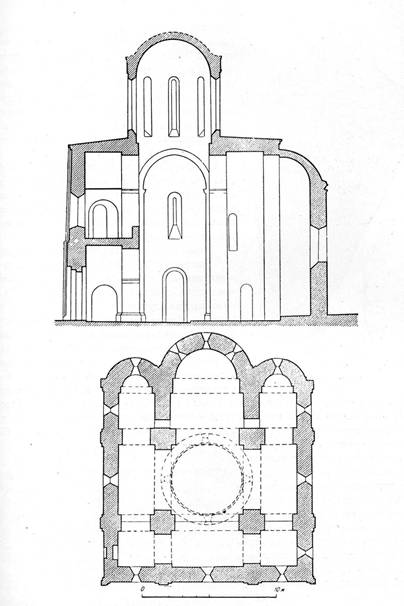

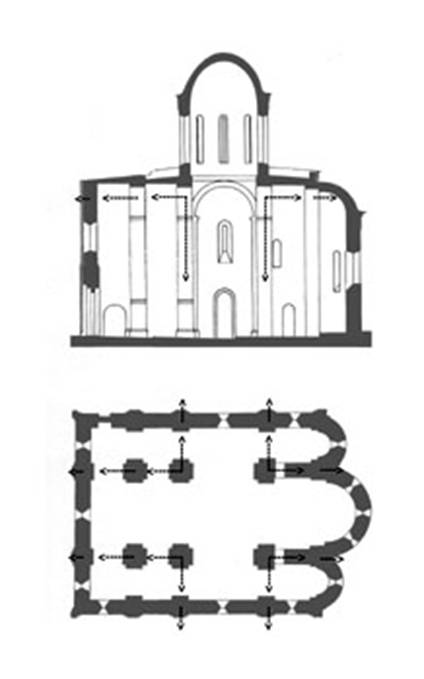

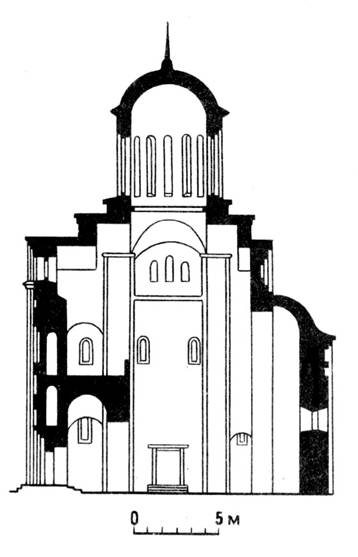

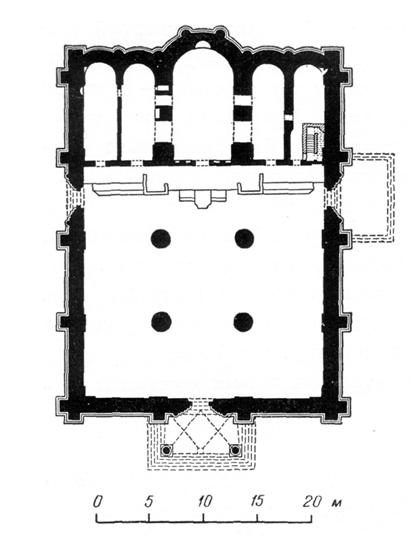

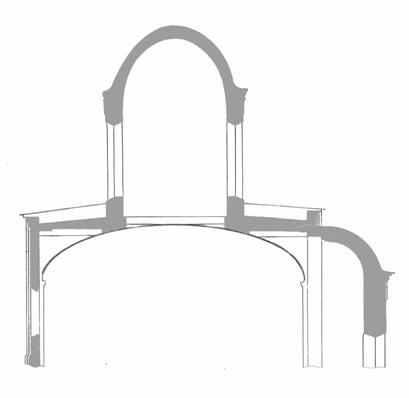

In this research we will offer and prove the overall picture of genesis and classification of Old Russian temples only by basic typological features – the plan and the ceiling. In architecture of Ancient Russia these features can't be considered separately from each other, because the most important type of temples – cross-in-square – is defined by both the plan and the ceiling (see Fig. 1). Taking secondary typological features into consideration will lead to the increasing of the quantity of types in a geometrical progression, and it can be a subject of other research, much more voluminous than the present one.

The final tables and schemes representing typological forming and classification of Old Russian temples by basic typological features are provided in the Conclusion.

1. Main terms and definitions

First of all it is necessary to specify some main terms which will be applied in our research.

We will start from the cross-in-square system. Due to the classical definition3, the kernel of such temple represents quadratic (generally – rectcorner) volume divided by four pillars into nine cells, or compartments (Fig. 14). The pillars are connected by the arches bearing the vaults. The center of the kernel is the subcupola quadrate over which the drum is located. The drum stands on supporting arches and is covered with the cupola. The subcupola quadrate is adjoined crosswisely by four rectcorner compartments – the cross sleeves, covered by the cylindrical vaults which resist to the drum pressure. Between them the corner compartments covered by the vaults of various forms are located. The corner compartments resist to the overturning pressure on the pillars of the supporting arches and cylindrical vaults.

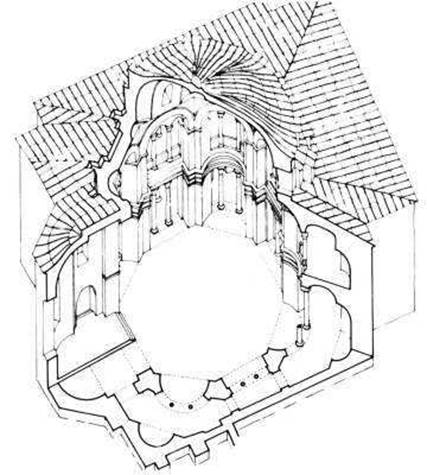

Fig. 1. The section and the plan of the classical cross-in-square temple with 4 pillars and 3 naves (on the example of Transfiguration Cathedral in Pereslavl-Zalessky).

The conditional direction of the longitudinal axis of Old Russian temples – from the West to the East, the crossing axis – from the North to the South5.

Formally each cross-in-square temple is a special case of the basilica – the rectcorner building consisting of odd number of the naves divided by longitudinal ranks of pillars. Respectively, the naves are also allocated in the longitudinal direction in the kernel of the cross-in-square temple. (The term "transept" for the crossing axis of such temple is used seldom).

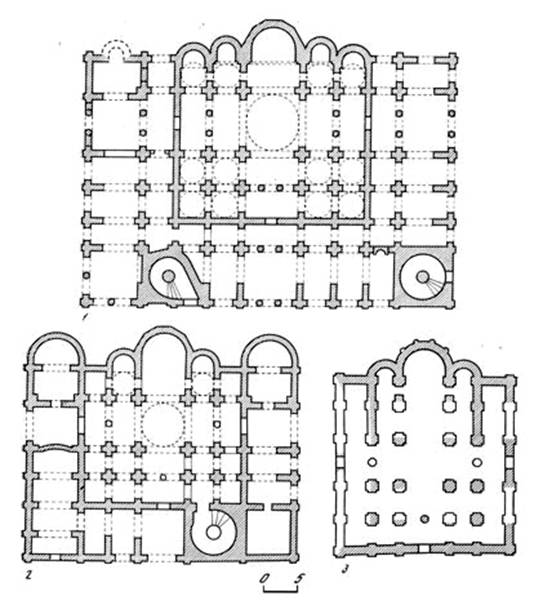

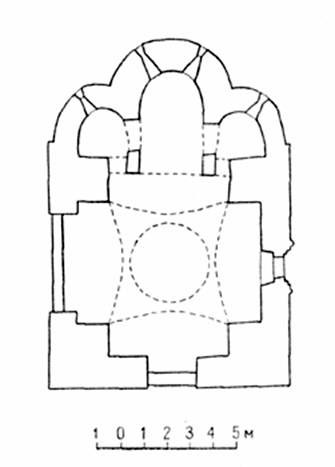

The kernel of the cross-in-square temple can be limited by the walls (the temple with 4 pillars) or by additional pillars. If there are additional pillars in the crossing direction, there is the temple with 5 naves (Fig. 26), if the case of longitudinal direction – with 6 pillars (Fig. 37), 8 pillars, etc.

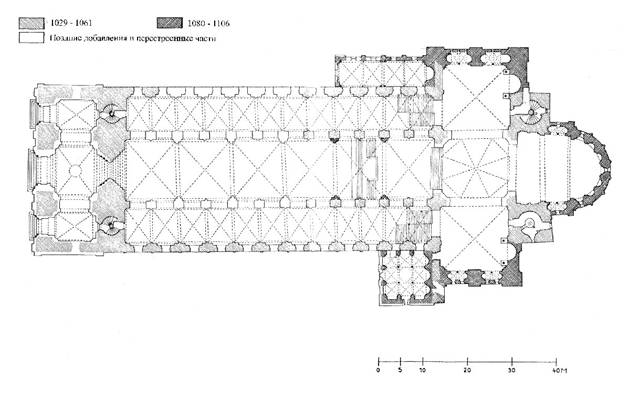

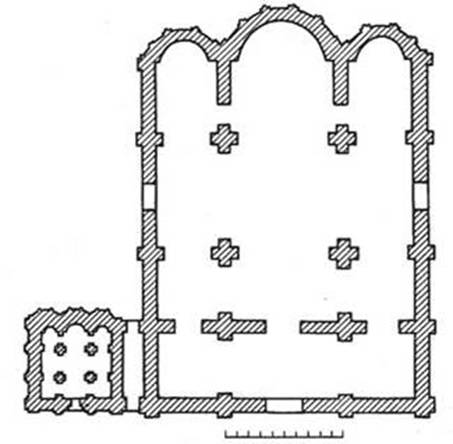

Fig. 2. Plans of the temples with 5 naves: the cathedrals St. Sophia in Kiev, Novgorod and Polotsk.

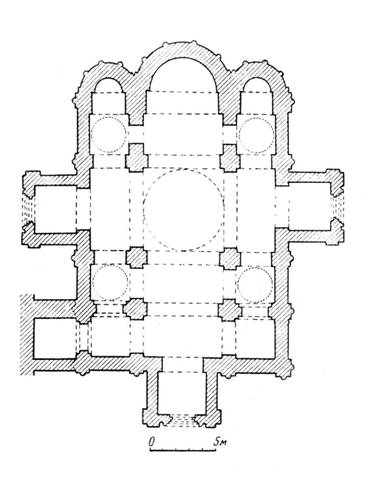

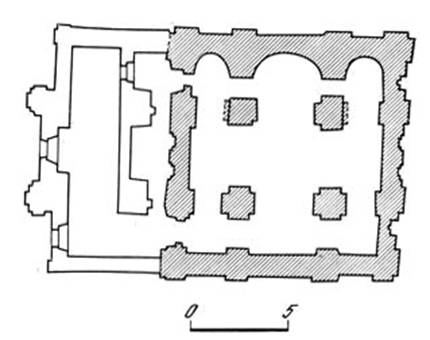

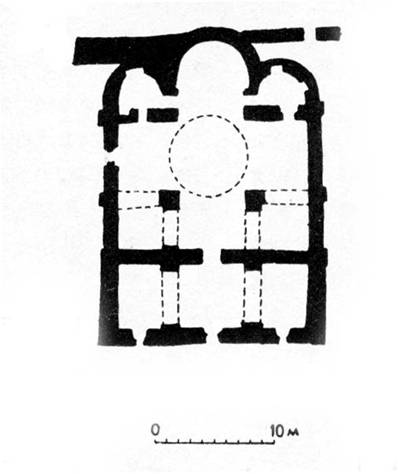

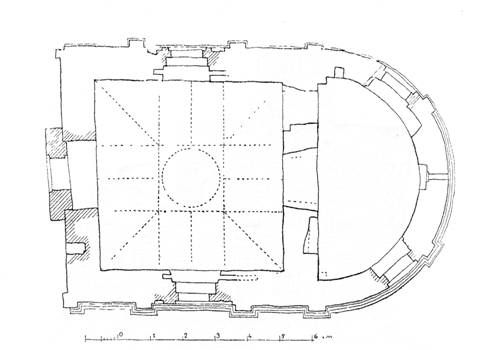

Fig. 3. The plan of Assumption cathedral built by Andrey Bogolyubsky in Vladimir. Reconstruction by the author. This temple had 6 pillars, 3 naves, 3 apses, 3 antechurches. The ladder tower from the northwest was connected to the next buildings.

The naos (the main volume of the internal space of the temple) can be adjoined by additional volumes: from the West – by the narthex, from the East – by the bema and the altar apse (apses).

We should note that if the antechurch adjoins the temple from the West, formally it is an analog of a narthex, and the terminological contamination takes place. The similar contamination arises also in the case that the antechurch is opened outside: then it is possible to call it an exonarthex or a porch. In this regard we will specify that the narthex and the exonarthex must be equal or nearly equal to the naos by width and (or) height, and the antechurches and the porches are considerably more narrow and (or) low. The latter ones, unlike the narthex and the exonarthex, can adjoin the temple also from the North and (or) from the South.

The narthex and (or) the bema can be opened into the naos of the temple and separated from it by a wall with apertures or by pillars. In this case there may be different interpretations: for example, it is theoretically possible to characterize Assumption Cathedral in Vladimir (Fig. 3) both as the temple with 6 pillars or with 4 pillars and the narthex.

The second option is traditionally8 used only if the narthex and (or) the bema are separated from the naos by a wall and (or) are expressed in external forms of the temple (for example, in Vladimir Assumption cathedral the narthex isn't separated by a wall and isn't expressed architecturally, therefore the temple is considered as having 6 pillars).

This point of view was called into question by A.I. Komech who wrote the following: "In the literature devoted to Old Russian architecture of the X-XV centuries the definition of structure of temples on number of pillars – 4, 6 or 8 – is widespread. Such classification distorts the real composite nature of monuments, besides it interprets forms incorrectly. It is distracted from the representations connected with the basilical constructions and is violent for the buildings of the cross-in-square type. As a rule, all Old Russian temples of the XI-XII centuries (except the simplest) – have 4 pillars, they may be with a narthex (this concept almost disappeared from our architectural descriptions) or without it"9.

Thus, according to A.I. Komech, Assumption cathedral built by Andrey Bogolyubsky in Vladimir (Fig. 3), St. George cathedral in Yuryev monastery in Novgorod, Assumption cathedral in Trinity-Sergius Lavra or St. Sophia Cathedral in Vologda must be called not having 6 pillars, but having 4 pillars and a narthex.

But we can't agree with A.I. Komech for the following reasons:

– the traditional point of view accurately defines existence or absence of an architecturally expressed narthex and (or) a bema (either in external forms or separated from the naos by a wall). In case of acceptance of the position of A.I. Komech we should have to specify, about which narthex and (or) bema we speak;

– speaking about "classical" temples with 4 pillars (for example, about Transfiguration cathedral in Pereslavl-Zalessky (Fig. 1), Intercession church on the Nerl or Saviour church on the Nereditsa), in the case of acceptance of the position of A.I. Komech we should have to specify every time that we speak about the temples without narthex and a bema;

– the point of view of A.I. Komech is applicable only for basilicas of the cross-in-square (Byzantine) type. Basilicas of West European type often also have a cupola over the crossing, and a large number of pillars, and both a narthex and a bema. For example, the Imperial Romanesque cathedral in Speyer (Fig. 4) has the cupola over the crossing, the narthex, the bema and 24 pillars. Respectively, according to A.I. Komech, we should claim that the basilica in Speyer has 4 pillars and 2 narthexes, and one of these narthexes has 20 pillars.

Fig. 4. The Romanesque cathedral in Speyer. Plan.

We see that the acceptance of the position of A.I. Komech unfairly complicates the terminology, confuses it and deprives of universality. In this regard we accept the traditional point of view on the interpretation of the quantity of pillars in any basilicas, including cross-in-square type.

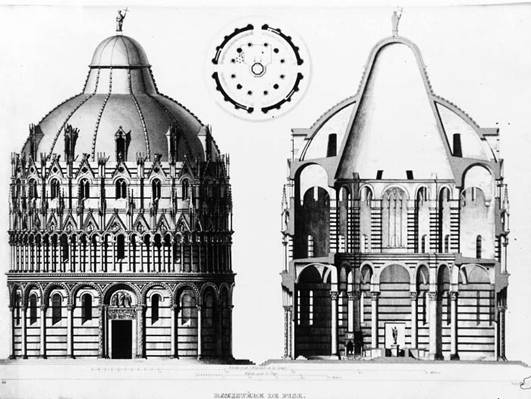

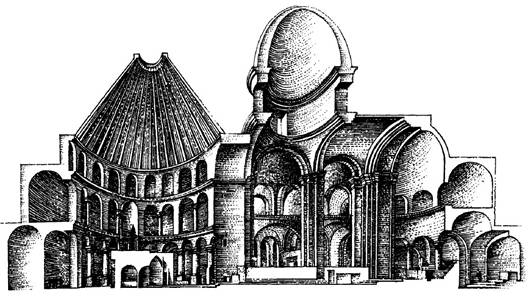

Now we should consider the term "cupola temple". So we will call the temple in which the cupola covers practically the whole naos. Respectively, such temple is usually centric (if doesn't consist of several isolated volumes, each of which is covered by the cupola). Two churches of the VI century – Sergius and Bacchus in Constantinople (Fig. 5) and San Vitale in Ravenna – are the examples of the centric cupola temples.

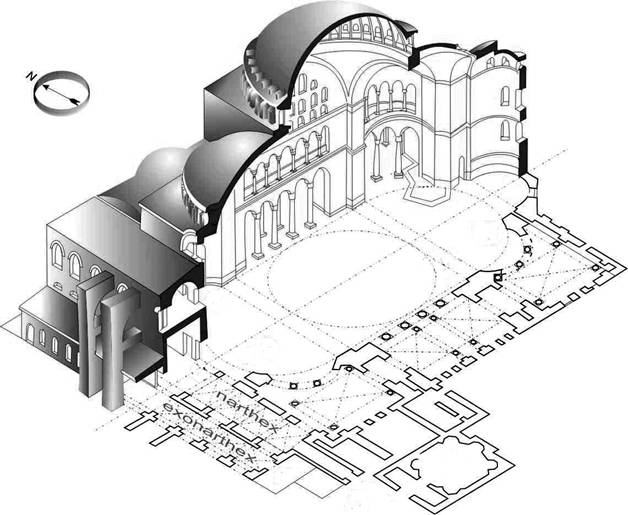

Fig. 5. Sergius and Bacchus church. Axonometrical section.

We should note that "General history of architecture" speaks about the church of Sergius and Bacchus as having 3 naves10, and, respectively, it turns out that the cupola covers not the whole naos, but only the middle nave. But this statement unfairly confuses terminology, because the initial meaning of the nave is the "ship", i.e. it always has the straight and extended form. Actually the church of Sergius and Bacchus is the cupola temple with the narthex, the apse and the roundabout gallery.

The plan of the cupola temple can have a form:

– of quadrangle (close to a quadrate);

– round (in the form of a rotunda), oktagonal, polygonal11, which we can unite under the conditional name "circumscribed circle".

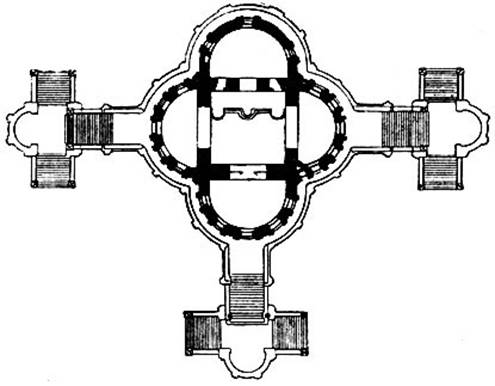

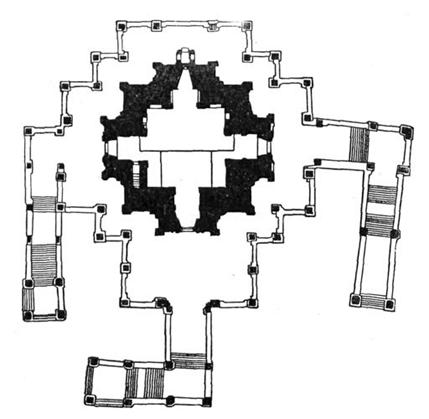

The special case of the plan of the cupola temple is the tetraconch (other name – quadrifolium). An example – Intercession church in Fili (1690-1693, Fig. 6). Here different interpretations are possible in case of the tetraconch has a quadrangle in its basis. (For example, I.L. Buseva-Davydova referred Intercession church in Fili to the type "octagon on quadrangle", as in this temple the semicurcles are separated from the naos by the walls with apertures and, therefore, these semicurcles are antechurches and apses12). In this regard, classifying a tetraconch with a quadrangle in its basis, it is necessary to specify if the semicurcles are opened into the naos or are separated from it by the walls.

Fig. 6. Intercession church in Fili. Plan.

If the tetraconch is not based on an unambiguously expressed quadrangle, such temples, as a rule, belong to the "circumscribed circle" type.

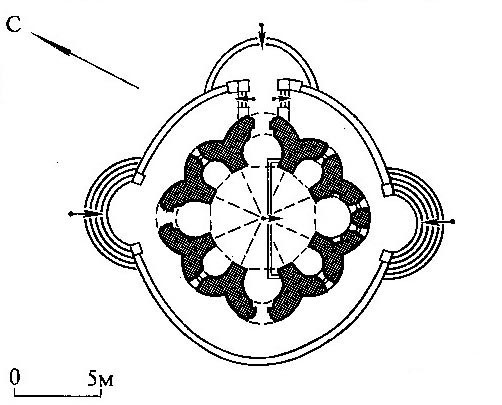

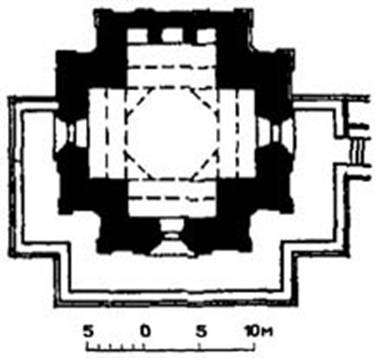

It is possible to refer to the "circumscribed circle" type also the temples with the “multileaf” plan (Pyotr Mitropolit cathedral in Vysoko-Petrovsky monastery, 1514-1517, Fig. 7), and also with cross-like plan (Pyotr Mitropolit church in Pereslavl-Zalessky, 1584-1585, Fig. 8), which are the special cases of polygonal temples.

Fig. 7. Pyotr Mitropolit cathedral in Vysoko-Petrovsky monastery. Plan.

Fig. 8. Pyotr Mitropolit church in Pereslavl-Zalessky. Plan.

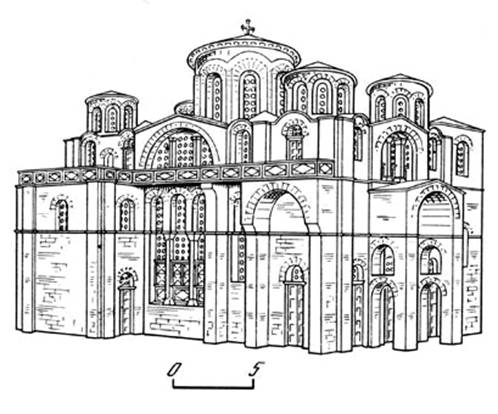

The term "cupola temple" can't be identified with the term "cupola basilica". Usually, speaking about the latter, we mean St. Sophia cathedrals in Constantinople (532–537, Fig. 9) and in Thessaloniki (the first half of the VIII century), Assumption church in Nicaea (the beginning of the VIII century) and some other Byzantine churches. That are the buildings of basilical type (stretched, with the middle nave higher than the lateral ones), covered by big cupolas only in the central part. In such cupola temple as we have spoken above, the cupola covers practically the whole naos.

Fig. 9. St. Sophia cathedral in Constantinople. Axonometrical section.

We have mentioned above the well-known in Russia cross-like plan of a temple (Fig. 8), but we can also discuss the term "cross-like temple" – the cross-in-square temple without the cupola. Neither in Russia, nor in Byzantium such temples existed. But here we have to address to one more branch of basilicas – West European.

Usually all medieval basilicas of the West European type (with big prevalence of length over width) in scientific and popular literature are called basilicas without specifications. Strictly speaking, it isn't quite right for the following reasons:

– the basilicas are also widespread in Byzantium and in Russia as cross-in-square temples (and in Byzantium – also as cupola basilicas);

– in a number of large West European basilicas the crossings are covered by the cupolas, which base on four pillars (as in Imperial cathedral in Speyer, Fig. 4), i.e. there are basic features of the cross-in-square system;

– if a West European basilica has one or more transepts, it ceases to be a basilica of the classical (ancient Roman) type.

In this regard it is always necessary to specify, about what basilicas we speak – the cross-in-square type, the cupola type or West European type. The latter, in turn, has subtypes: with transept and without it.

In the case of presence of one or more transepts in the basilica of West European type it is possible to introduce the concept "cross-like" temple and to use together with the term "Latin cross" which is widely accepted. The cupola over a crossing, even if is present at such system, isn't an essential element in the image of the temple, and this is the fundamental difference of "cross-like" ("Latin cross") basilicas from the basilicas of both cupola and cross-in-square types.

For the West European basilicas without transept it will be useful to specify that we speak about the basilicas of classical type.

In this research we will mention the construction materials of the temples only in the case of wooden architecture or when this is demanded by the context. "By default" we shall speak about stone architecture (by which we will generally mean the temples built of natural stone, plinthite, shaped brick or in the mixed technology – so called "opus mixtum").

Time frames of Old Russian architecture and, respectively, of this research are limited to the end of the XVII century. We will generally call the subsequent eras "Modern times".

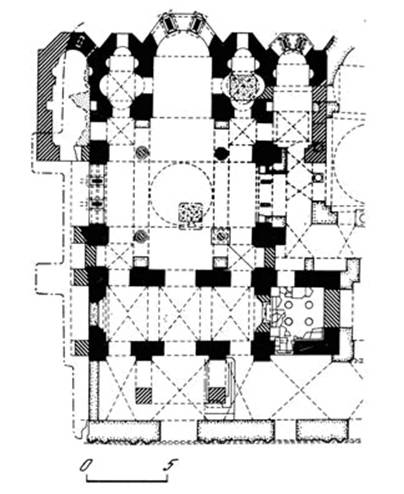

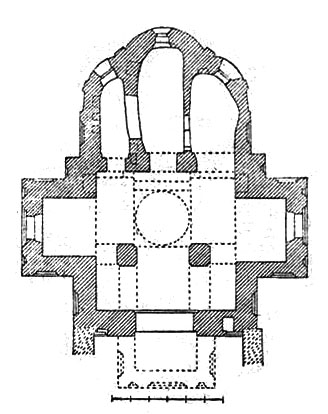

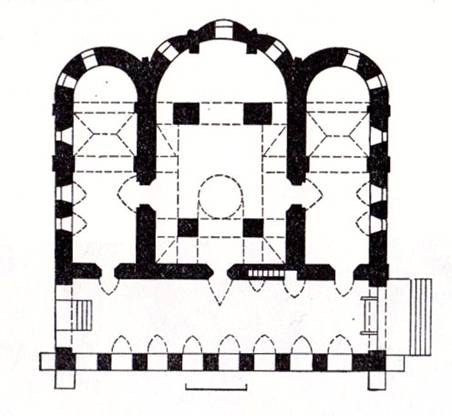

2. About the reasons of evolution of Byzantine cupola churches to the cross-in-square type

Evolution of architectural forms of Byzantine basilicas from the cupola type (an example – St. Sophia cathedral in Constantinople, Fig. 9) to the cross-in-square type (an example – the church of Holy Virgin in the monastery of Lips in Constantinople, 908, Fig. 1013, 1114) within the V-X centuries is studied in details in a number of scientific works15, and here we will not stop at this question, especially because it treats the main subject of our research – the genesis of Old Russian church architecture – only indirectly: Ancient Russia at a turn of the X and XI centuries apprehended already created result of this evolution and never came back to the cupola basilicas. The question of the reasons for which in Byzantium such evolution took place, is more important for our research.

Fig. 10. Church of Holy Virgin of the monastery of Lips in Constantinople. Reconstruction by A. Migo.

Fig. 11. Church of Holy Virgin of the monastery of Lips. Plan.

St. Sophia cathedral of 532–537 in Constantinople remained the biggest temple of the Middle Ages for more than one thousand years, up to the construction of St. Peter's Cathedral in Rome (if not by the square, then by the height of the naos and the diameter of the cupola). The height of St. Sophia cathedral is 56 meters, the diameter of the cupola – 31 meters.

There were no essentially new basic architectural forms in St. Sophia: the basilical and cupola types came (though indirectly16) from Ancient Rome, and the diameter of the cupola of Pantheon (43 meters) is even more than in Sophia. But the combination of basilical type and the enormous cupola in Constantinopolitan cathedral together with the very big height of the naos and truly ingenious architectural figurativity allowed to build an original masterpiece which, undoubtedly, served as a sample for further architecture of Byzantium.

But the subsequent Byzantine construction eras were unable to reproduct Constantinopolitan Sophia in all its magnificence (first of all concerning the diameter of the cupola, which predeterminates other sizes of the cupola basilicas). The empire reduced, the construction funding shortened, the construction technique degraded, the requirements to construction decreased. Respectively, cupolas couldn't but decrease. In this regard E.E. Golubinsky considered that the cross-in-square system succeeded the cupola system because it provided the similar spaciousness of the temple with the smaller diameter of the cupola17.

But E.E. Golubinsky's position doesn't answer the vital issue: wasn’t then better to refuse of the cupola at all? The cupola causes not only a number of constructive problems, it together with the drum makes additional load on the arches and pillars of the temple. Basilicas – and classical, and of "Latin cross" type – perfectly do without cupolas, and have much higher reliability and simplicity of construction18.

N. I. Brunov believed that the cupola in Byzantine churches was necessary as it symbolized the sky, "framed and finished the liturgical action" 19. In "General history of architecture" N.I. Brunov's position was expressed even more consistently: firstly the requirements of the liturgy were expressed in the need of existence of a cupola over the ambon in the center of the temple, and of the organization of processions around it. The main accent was postponed from the altar to the cupola, and (we quote) "the simple worship was replaced by the dramatized cult" 20. Then, according to the researcher, the cross-in-square system formed – on the basis of the need to subdivide a temple interior into the central part, with the ambon in the middle, and into the surrounding space accomodating attendees at some distance from the ambon. The role of such divider was played by the pillars, and thus "the idea of hierarchy" 21 was expressed.

We can't agree with this position because any other type of vaults could play the cupola role in the liturgy, and the latter would have lost nothing. For example, in "Latin cross" temples the crossings correspond to subcupola squares of Orthodox churches. In general, the liturgy in non-cupola Catholic temples of the West isn't less dramatized, the praying people are much more separated from the priests, the liturgy is visible much better from the sedentary places in the naves.

A.I. Komech, writing about the reason of evolution of the cupola basilica into the cross-in-square type, partially supported the position of N.A. Brunov22, but fairly considered that "such transformations didn't demand, however, the radical change of the structure, since they were quite possible in basilicas" 23. In this regard A.I. Komech put forward his own reasons connected with symbolics and esthetics of the temples24. He briefly described the essence of his position so: "It is impossible to doubt that the prevailing of the cross-in-square temples is connected with their compliance to certain world outlook base where symbolical ideas and esthetic expressiveness of a ceremony were of great importance, even contrary to some inconvenience" 25.

But it is quite improbable that works of philosophers and theologians, who gave to this or that architectural element this or that symbolical interpretation, could affect a choice of this or that constructive system of the temple, especially so difficult in construction and labor expanditures, as the cupola and cross-in-square systems.

Besides that, history of world architecture knows no facts that some theologian decided that in the interests of symbolics (or any theological theory) the temple has to receive this or that new element or this or that new form, coordinated the position with the funder and ordered to the architect to build quite so, not differently. The similar facts even concerning priestly vestments and liturgical arrangement are unknown to us, and in architecture, which is much more expensive and difficult from the technical and organizational point of view, such situation can't be even imagined.

Symbolical ideas, as well as theological theories and world outlook bases in general, could influence the formation of the tradition only indirectly. Conditionally speaking, the funder orders, the architect builds, the society estimates, the interpreters interpret, the results of the estimation and interpretation are perceived and in a varying degree considered by the next generation of funders and architects, etc.26

Innovations in temple architecture always in a varying degree are the withdrawals from the tradition, and, respectively, they can't be explained by any symbolical interpretation. The talent of architects, and art taste of customers, and progress of construction technology, and change of esthetic preferences of society, and ideological tasks, and loans from other cultures and styles, and many other factors can generate these innovations, up to especially utilitarian purposes (for example, the need to increase the spaciousness of the temple). Financial, and personnel, and other restrictions which can dispose to non-standard decisions also can play a role here.

The usage by the researchers of symbolics as justification of the ways of genesis of architectural forms of temples has one more negative methodological aspect. If in the ancient times the symbolics even had some influence on the genesis of architectural forms (as we’ve seen, that isn't proved), we in each case don't know, which exactly symbolics how influenced. No documentary certificates on this subject remained, and all efforts of the modern researchers in the search of symbolics of these or those architectural features and elements of temples, as a rule, conduct to exclusively subjective opinions, which are easily disproved not only by statistics and the facts, but also by promotion of other subjective opinions, which look no less convincingly27.

As for esthetics, it is even more conditional than symbolics, and the application of esthetic arguments for justification of appearing of new architectural forms is also unfairly from the methodological point of view. There is no doubt that the esthetic preferences influenced architectural forms at all times (otherwise the mankind wouldn't have built anything except especially utilitarian constructions), but we can judge medieval tastes only indirectly – through already accomplished facts of their natural realization. Respectively, all efforts of the modern researchers in the search of the esthetic reasons of the appearing of these or those elements of medieval temples, as a rule, conduct only to the ascertaining that the architect and the funder wanted to build something beautiful.

And in the context of this research, esthetics could influence the genesis of the cross-in-square system rather negatively, than positively: it is unlikely that the cross-in-square temples could ever seem to someone more esthetic than the cupola basilicas, among which there was the unique masterpiece of universal value (possibly, the most beautiful temple of all times and countries) – Sophia in Constantinople.

In connection with all aforesaid we can put forward the other vision of the reasons why the cupola system in Byzantium evolved in the cross-in-square. We assume E.E. Golubinsky's position (he, as it have been said above, considered that the cross-in-square system succeeded the cupola basilics because it provided the similar spaciousness of the temples with the smaller diameter of the cupolas)28, but with an essential specification: it was necessary to keep in the temple at least rather small cupola, because the latter was not just an important architectural and symbolical element, but the basis of the tradition of Byzantine church architecture.

The latter conclusion is based on the following observations:

– the vast majority of Byzantine churches had cupolas, the non-cupola basilicas were constructed very seldom (for example, the church in Mesopotamic town of Sal, the VI century29; Syrian basilicas of the VI century in the towns of Ruvey, Turmanin, Taphka30; St. Demetrius church in Thessaloniki, the VII century; etc.);

– the cupolas were constructed everywhere in spite of the fact that they not only caused a number of problems at their construction, but together with the drums created additional load on the arches and pillars of the temples. Basilicas, both classical and "Latin cross", perfectly did without cupolas and had much higher reliability and simplicity of construction31;

– Sophia in Constantinople with its enormous cupola was not only the largest temple, but also the cathedral and imperial temple, so this tradition could have also formal confirmation in the form of direct instructions of the Emperor and (or) Patriarch.

The direct ban in Byzantium for non-cupola temples building is possible32, but the facts of construction of such temples in provinces are against this version. Such construction took place seldom, but nevertheless took place. However, it is impossible to exclude also the probability of violation of such ban by local authorities with the link, for example, to the absence of specialists in cupolas construction: not for nothing, as N.I. Brunov fairly noted, architecture of Byzantine provinces and the capital is quite different33.

And still, concerning architecture of Byzantium, we meanwhile can't consider as proved the existence of direct state or church instructions on obligatory cupolas construction in the temples and (or) a ban on construction of non-cupola temples. Concerning architecture of Ancient Russia – we can, and about this see further.

3. About the ban on non-cupola temples in Ancient Russia

The adoption of Byzantine Christianity in Ancient Russia caused the adoption also of Byzantine church architecture34. But the problems of missionary work in the large, formerly pagan country caused local specifics: there was the need of the fastest construction of the greatest possible number of large, representative and capacious stone temples in the conditions of acute shortage of the qualified construction workers. (The short-living, fire-dangerous and having rather small naos wooden temples, about which we will talk in Chapters 8 and 10, solved this problem only partially).

It can seem that the simple and capacious basilicas of West European type, which, as we have seen in Chapter 2, sometimes were under construction also in Byzantium, could be the optimal solution here. But, nevertheless, all stone Old Russian temples had cupolas or their modifications (including hipped roofs, see Chapter 8).

At the primary stage of formation of Old Russian architecture the attempts of increasing of the internal space consisted in the increase of the number of the naves to five, as in St. Sophia сathedrals in Kiev, Novgorod and Polotsk (in Byzantium, as A.I. Komech fairly noted, there were no temples with 5 naves35), and the number of the pillars in the central nave – to eight, as in St. Sophia in Polotsk (see Fig. 2).

But the increase of the number of the naves, as well as the number of the pillars in the temples with 3 naves, in the conditions of the cross-in-square system lead to the decrease of constructive reliability and the requirements to qualification of the construction workers.

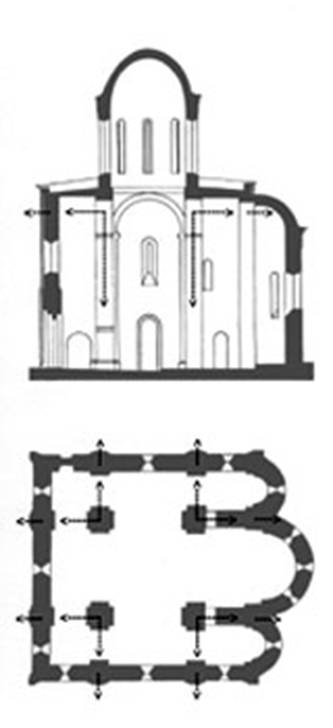

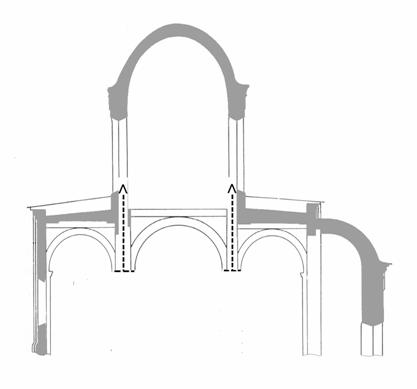

The matter is that in the kernel of the cross-in-square temple, the drum-supporting arches under the weight of a drum create overturning efforts on four pillars in the horizontal plane (Fig. 12). Therefore, the the arches of lateral naves play the role of the arkbutans, and the external walls – the role of the buttresses.

Fig. 12. The conditional scheme of distribution of the load from the drum on the pillars and walls of the cross-in-square temple with 3 naves and 4 pillars.

And when at the increase of the number of the naves or the pillars in the central nave (Fig. 13) the additional pillars instead of one of the walls appeare, they become much more exposed to the deformations because of the "overturning" efforts in the horizontal plan, and the reliability of the construction significantly decreases. The installation of additional drums for illumination of the additional compartments aggravates the problem of the "overturning" loadings.

Fig. 13. The conditional scheme of redistribution of the load of the drum to the pillars and walls at hypothetical transformation of the cross-in-square temple with 4 pillars into the temple with 6 pillars. It is visible that two additional pillars bear the considerable "overturning" load in the horizontal plan, and the wall behind them (a much more reliable constructive element) is almost unloaded. Similar redistribution of loads takes place at the increase of the number of the naves and at further increase of the number of the pillars in the central nave.

Thus, in the cross-in-square temple the increase of the number of the pillars leads to the same consequences as the increase of the internal space: in the case of identical central heads the temple with 3 naves and 6 pillars is less reliable than the temple with 3 naves and 4 pillars.

Probably, the foresaid also became the reason that both in Byzantium and in Ancient Russia the tendency to multi-pillar temple interior never took place. Instead of this, the increase of the internal space of the church buildings was achieved by the galleries, antechurches and other extensions36. But such extensions most often spoiled the appearance of the temple, deprived it of solemnity.

In the West European basilicas, where (with rare exception) the pillars carried only the arches, but not drums and cupolas, the increase of the internal space by the increase of the number of the pillars and naves didn't seriously influence the construction durability. However, Old Russian masters didn't apprehend this experience even in the conditions of the full inclusiveness of architecture of Ancient Russia in world architecture since the middle of the XII century (see Chapter 4 and further). Up to the latest time no cupola basilicas were constructed in Russia (as we have seen in Chapter 4, in Byzantium they were built, though occasionally).

The conclusion from this situation can be the following: Byzantine tradition of the obligation of existence of a cupola in the temple turned in Russia into the total ban of non-cupola temples.

In history of architecture in Soviet period the tradition of interpretation of forms and elements of church architecture was consolidated according to construction and technological features, style genesis, art taste, economy, policy and a set of other factors, except an important one: direct influence of Orthodox Church.

But in the end of the X – the beginning of the XI century the Church already existed for the second thousand of years. If to consider since the V century, when it turned into the closed hierarchical system with the settled dogmatic base and the regulated ceremonies, about six hundred years had passed – the considerable term, too. The dependence of the Russian metropolitanate till 1589 dictated especially rigid approach of the Church to the subtleties of architectural style, because all more or less serious innovations were to be coordinated with the Constantinopolitan Patriarch. And the latter understood that typological and stylistic features of temples carried out "visible communication" of Russian Orthodoxy with Byzantium, and the concessions in any of these questions meant the movement of Russian Church to independence, very undesirable for the ambitions (and the economic interests) of the Patriarch.

Perhaps, in this regard the ban on non-cupola temples was undertaken. This ban, in whatever form it took place, was accepted in the first decades of existence of Christianity in Russia, otherwise non-cupola basilicas would have appeared, at least in small quantity37. In the next centuries of formation of Old Russian architecture this ban turned into obligatory tradition, and hardly someone already remembered its roots.

How this ban correlated with the hipped-roof temples, we will talk in Chapter 8. Here we should just note that the only exception which was made in the ban on the non-cupola temples, – the wooden izba-like churches. Perhaps, the latters were considered in Ancient Russia as "temporary". Perhaps, they couldn't be forbidden at all desire, because of absence of enough qualified construction workers for the building of more "refined" types of wooden architecture in the majority of villages.

It is important to note that it is already the third (and chronologically – the first) ban of Russian Orthodox Church on these or those architectural features of temples. The church at the beginning of the XIV century forbid the decoration of temples by Romanesque-Gothic zooanthropomorphous sculptural decor (i.e. the decor with the images of people and animals; this decor should be distinguished from the ornamental decor)38. In the middle of the XVII century the construction of the hipped-roof temples was actually forbidden (about this ban see in details in Chapter 9).

Now, having considered the reasons of absence in Russia of such diverse and worldwide accepted temples as non-cupola basilicas (including the West European type), we can pass to consideration and classification of those basic types which existed in Old Russian church architecture.

4. Two sources of architecture of Ancient Russia and two first main types of Ancient Russian temples

The first source of Old Russian church architecture is well-known: that is architecture of Byzantium39, which was the origin of the type of temples which we can call "the first basic type": cross-in-square, with 3 naves and 6 pillars. (For descriptive reasons we will give to each type and subtype hierarchical digital marks; this type is marked by figure 1).

In Russia, the tradition of construction of the temples with 3 naves and 6 pillars is led40 from Kiev Pechersk Lavra Assumption cathedral, which was constructed in 1073–107741 under the guidance of Byzantine builders42 (Fig. 1443). This temple became, in turn, the direct continuation of the typological and stylistic line of other temples which had 3 naves, but didn’t have so clear and accurate structure, – Transfiguration cathedral in Chernigov and probably Kiev Tithes church which were also constructed under the direction of Byzantines44.

Fig. 14. Kiev Pechersk Lavra Assumption cathedral. Plan.

Strictly speaking, Assumption cathedral has no 6 pillars, but 4 pillars and the narthex, as the latter was architecturally expressed45. But this temple thanks to its clear and accurate structure served as a sample for a large number of Old Russian temples with 6 pillars (as well as the temples with 4 pillars and the narthex), mainly of the bishop’s and cloister’s cathedrals46 such as the cathedral of St. Michael’s Golden-Domed monastery in Kiev (1108-1113), the cathedral of St. George’s monastery in Novgorod (1119-1130), Assumption cathedral in Vladimir (1158-1160), the cathedral of Ivanovsky monastery in Pskov (the 1140th), Smolensky cathedral of Novodevichy monastery (the middle of the XVI century), St. Sophia cathedral in Vologda (1568-1570), the cathedral of Ipatiev monastery (1650-1652) and many others. (Special typological interpretation of 6 pillars took place in Moscow Assumption cathedral by Aristotle Fioravanti, but we will talk about in details in Chapter 6).

The second source of Old Russian architecture – West European Romanesque – is still known much worse than the first one. Its importance was belittled for the ideological and political reasons in pre-revolutionary time (according to the doctrine "Orthodoxy, autocracy and the nation") and in Soviet period47.

Underestimation of Romanesque source created the serious problem concerning the positioning of Old Russian architecture in history of world architecture. The matter is that architecture of Byzantium is usually perceived as the self-sufficient, primary, "basic" phenomenon, and architecture of Ancient Russia – as something secondary. The perception (firstly in the West) of whole Old Russian architecture in the world context as "suburban" and "provincial" became the inevitable consequence of such approach.

But actually the influence of Byzantium on the architecture of Ancient Russia was defining only till the middle of the XII century, and then architecture of the forming new center of the country – Vladimir-Suzdal Grand duchy – came under influence of West European Romanesque.

The main feature defining so-called "Russian Romanesque" 48 is the construction of smooth-cut white stone. The vast majority of Romanesque cathedrals in the centre of Sacred Roman Empire – Germany – were stone, only minor civil constructions and small provincial temples were built of brick at that time. Romanesque temples in Northern Italy were, as a rule, built of brick, but either were faced with stone (as the city cathedral in Modena), or such facing was provided, but wasn't made for various reasons (as in Sant Ambrogio cathedral in Milan), or was made not completely (San Michele church in Pavia).

In Byzantium (except some provinces) the temples were built of plinthite or in the mixed technology – "opus mixtum". The same – of plinthite or in mixed technology – was also pre-Mongol construction of all Old Russian lands, except Galich and Suzdal. In Galich white stone construction began at the boundary of the 1110s and 1120s49, in Suzdal a bit later – in 115250.

Other major elements of Romanesque architecture, which embodied in pre-Mongol architecture of North-Eastern Russia, are the sculptural decor of Romanesque (zooanthropomorphous) type and perspective portals.

The author of this research repeatedly showed51 that so-called "Russian Romanesque" in North-Eastern Russia began with construction by Yury Dolgorukiy in 1152 of five white stone temples, of which Transfiguration cathedral in Pereslavl-Zalessky (see Fig. 1) and the church of Boris and Gleb in Kideksha remained.

Yury Dolgorukiy for the first time started using in Suzdal land European technology of construction of natural stone. The ornamental decor of "universal" Romanesque type, which is found on a number of temples in Western Europe, took place in Pereslavl-Zalessky and Kideksha. In the church of Boris and Gleb in Kideksha we see also the perspective portal.

According to the researches of the author, the direct source of architecture of Yury Dolgorukiy was the key Romanesque temple – Emperors’ cathedral in Speyer (Fig. 4). The basis for such conclusion was the similarity of the construction of walls and bases, ornamental carving, some other stylistic and constructive features52. In the central crossing of this cathedral even the cross-in-square scheme with cross-like pillars was realized. Also the factor of exclusive all-European importance of Emperors’ cathedral is important.

The author also showed that the architect, who came to Andrey Bogolyubsky from the Emperor Friedrich Barbarossa, was invited still by Yury Dolgorukiy during his Kiev reigning, and that Yury achieved the permission of Orthodox Church for Romanesque sculptural decor of zooanthropomorphous type, but he had no time to arrange such decor on his temples53.

So-called "Russian Romanesque" gained the development in Andrey Bogolyubsky times when mentioned above Friedrich Barbarossa's architect worked in Russia54 and when in architecture of Vladimir-Suzdal land appeared such typically Romanesque features as the zooanthropomorphous sculptural decor, the pilasters with semi-columns, the attic profile of socles, the bases with corner "horns", the developed perspective portals, three-part windows, arkature-columnes belts, cube-like capitals and so forth.

And the existence of not one, but two basic sources of Old Russian architecture allows to speak about it not as about "late provincial Byzantium", but as about the independent phenomenon of universal value.

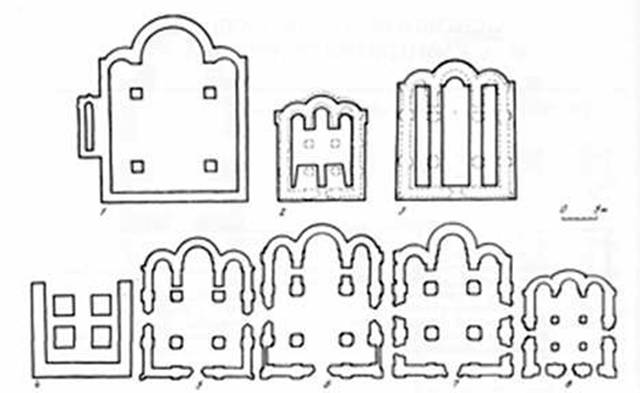

But was Yury Dolgorukiy's architecture only "imported", i.e. was it only an alloy of Romanesque technological and figurative solutions with Byzantine cross-in-square system? No way.

Dolgorukiy's temples have 4 pillars and 3 naves, no narthex, bema, antechurches or galleries, i.e. these are the cross-in-square temples of "typologically pure" type, which were earlier built both in Byzantium and in Russia extremely seldom, and in Western Europe were not built at all.

N.N. Voronin wrote that this type of the temple was widespread before Dolgorukiy55. But we can't agree with the researcher: actually only seldom cases of construction of the cross-in-square temples with 4 pillars and 3 naves in Russia before the middle of the XII century are known, and all these temples very significantly differed from Dolgorukiy's temples:

– the above-gate Trinity church of Kiev Pechersk Lavra (1108, Fig. 1656) formally belongs to the centric temples with 4 pillars, but actually, as A.I. Komech fairly noticed, this temple had 2 pillars: because of absence of sufficient space on the gate, the builders had to refuse of the apses, but the niches remained in the interior, and the whole eastern part of the temple turned into the altar57;

Fig. 15. Trinity above-gate church in Kiev Pechersk Lavra. Plan.

– from St. John’s church in Peremyshle (1119–1124) only the bases remained, which by technology (but not by the plan and by the size) are similar to the bases of Yury Dolgorukiy's temples (Fig. 1658). But the probability of St. John’s church construction in white stone technology is low: its walls and pillars are too thin in comparison with the flights of the arches. Perhaps, it was built of stone, but covered by wood, as very many West European temples;

Fig. 16. Plans of Galich and Suzdal temples (according to O.M. Ioannisyan):

1 – St. John's church in Peremyshle;

2 – the church in Zvenigorod;

3 – the church of Saviour in Galich;

4 – the church in "Tsvintariski";

5 – Transfiguration cathedral in Pereslavl-Zalessky;

6 – the church of Boris and Gleb in Kideksha;

7 – St. George's church in Vladimir;

8 – Ordination church on Golden Gate in Vladimir.

– nothing remained of the temple in Zvenigorod of Galich land, except the bases of similar technology (Fig. 16), which raise doubts in its belonging to cross-in-square type. Two pillars (on Fig. 16 designated by the dotted line), included by O. M. Ioannisyan into his reconstruction with the purpose to present the temple as cross-in-square, find no archaeological confirmation, at least in the form of the remains of the bases.

Till 1152 (i.e. either shortly before Dolgorukiy's temples or along with them) in Galich the white stone church of Saviour was built, and it was similar to Yury's temples by the plan, technology of construction and the decor (Fig. 16). But, firstly, we know nothing about its appearance, secondly, it is quite possible that this church and Dolgorukiy's temples were built by the same craftsmen59, i.e. we have the right to include this church into the group of temples of Yury, as Dolgorukiy and the prince Vladimirko of Galich were allies, and Yury was more senior on the age and on the princes’ hierarchy, and had incomparably higher standing in Russia60.

We know some cross-in-square temples with 4 pillars in Byzantium (Atik Dzhami, the middle of the IX century; the church of the Virgin in the monastery of Lips, beginning of the X century, Fig. 11; the church of the Virgin Halkeon in Thessaloniki, the beginning of the XI century; etc.). But this type, firstly, was seldom, and secondly, the view at the plans of these temples shows the complexity of the structure and the lack of clarity and integrity which are characteristic for Dolgorukiy's temples. The same, only in even bigger degree, we can say also about the appearance of Byzantine churches (according to A.I. Komech, these temples had "difficult and polysynthetic shape" 61; Fig. 10).

Thus, we can consider the basic type of temples of Dolgorukiy if not unprecedented, then used earlier extremely rarely and in other forms. And the combination of integrity of the plan with integral and tower-like general appearance of Dolgorukiy's temples had no precedents in the world.

The integrity of appearance of the main volume of the temple isn't a distinctive feature of Romanesque (and furthermore of Gothic). West European basilica, as a rule, makes quite shapeless impression in comparison even with Byzantine churches, without speaking about Dolgorukiy's temples which look like hewn of an integral white stone.

The same we can say about tower-like appearance. The main volume of the West European basilicas, both Romanesque and Gothic, isn't tower-looking at all (most likely, the position of G.K. Wagner who wrote that tower-like appearance of Russian temples was caused by influence of Gothic62 was affected by West European belltowers; but actually the main volumes of the basilicas in Western Europe have flat silhouettes)63.

A certain integrity and tower-like appearance of Romanesque and Gothic basilicas was caused only by the belltowers. The temples of Dolgorukiy, conditionally speaking, were both basilicas and towers.

Therefore, with Byzantine cross-in-square type and a number of Romanesque construction methods and stylistic features, the main contribution to appearance of the temples of Yury Dolgorukiy nevertheless was made by the Russian builders, and that predetermined uniqueness of these buildings.

N.N. Voronin wrote about Dolgorukiy's temples: "Development of this type of the temple didn't present any technical or architectural difficulties; on the contrary, it was only reduction and "the simplified edition" of the cross-in-square temple with 6 pillars" 64. In "History of Russian architecture" Dolgorukiy's temples were characterized as "unpretentious" 65. But we can't agree with such estimates, because above we have shown that the number of innovative typological and figurative solutions in Dolgorukiy's temples is considerable, moreover, the construction of these temples was ingenious creative action of Old Russian builders. Byzantine cross-in-square system, on the basis of which this type of temples was created, was, firstly, only the restriction (see Chapter 3), and secondly, it was radically creatively revised. These temples were optimal by the combination of the criterias of reliability, demanded qualification of the builders, the square of the naos, the integrity of appearance and the altitude.

The optimality of such type of the temples is confirmed by the fact that it became the most mass in Ancient Russia. The centric cross-in-square temples with 4 pillars were constructed in a large number in all times in all regions of Russia. Such masterpieces of Russian architecture, as the church of Intercession on the Nerl (115866), the church of Saviour on the Nereditsa (1198), Annunciation cathedral in Moscow Kremlin (1489), Assumption cathedral in Dmitrov (the first third of the XVI century), Trinity church in Chashnikovo (the middle of the XVI century), the cathedral of Pafnutyev-Borovsky monastery (1586), the church of Transfiguration in Bolshie Vyazemy (1584-1598), the Big cathedral of Donskoy monastery (1686-1698) and many others belong to this type67.

Due to the above, we refer the centric cross-in-square temples with 3 naves and 4 pillars to the second main type of Old Russian church architecture (digital marking – 2). It is possible to consider Transfiguration cathedral in Pereslavl and the church of Boris and Gleb in Kideksha to be the first typologically formed temples of this type.

5. Types of Old Russian temples derivative of the second basic type

It is possible to allocate in evolution of the second basic type (centric cross-in-square temples with 4 pillars) a number of derivative types, each of which became an important typological component of Old Russian architecture.

The temples of the first derivative type from the second basic (digital marking – 2.1) are the cross-in-square temples with 4 pillars, which appeared at the turn of the XII-XIII centuries with the raised supporting arches (other versions of the name of this type – with arches raised by the steps, with step arches, with step vaults).

In principle, the system of the arches raised by the steps was applied earlier not once (though in other types): in a number of West European basilicas where the average nave was most often higher than the lateral, and in Sophia of Kiev (the first half of the XI century), and in the cathedral of Mirozhsky monastery (before 1156). N.N. Voronin fairly called the cathedral with 6 pillars in Spaso-Evfrosinyevsky monastery in Polotsk (before 1159) the direct transition to this type68.

It is possible to consider Pyatnitsky church in Chernigov (the turn of the XII-XIII centuries, Fig. 17) and the cathedral of Archangel Michael in Smolensk (1191-1194) the first typologically formed temples of type 2.1. Further such temples as Pyatnitsky church at the Market in Novgorod (1207), the first Assumption cathedral in Moscow (1326–132769), the cathedral of Andronikov monastery (1425–142770), the cathedral of Nativity monastery in Moscow (the beginning of the XVI century), Assumption cathedral in Staritsa (1530) and many other temples were built with the raised supporting arches.

Fig. 17. Pyatnitsky church in Chernigov. Section.

The appearing of the temples with the raised supporting arches has two reasons.

The first – increase of constructive reliability71. In the case of the raised supporting arches, the vaults of the lateral naves are loaded also from above, not only from the sides (as in the classical cross-in-square scheme presented by the first and second main types, where the supporting arches and the vaults of the lateral naves are approximately at one level; see Fig. 1, 12, 13). Therefore, the step gradation of the arches gives more even distribution of load from the drum to the elements of the quadrangle (and, respectively, higher constructive reliability) than the "classical" scheme – with supporting arches at the level of the vaults of the lateral naves.

Thus, the raised supporting arches gave possibility to achieve the increase of the internal space of the temples without decrease of reliability, and also without the use of more perfect construction technologies and more qualified construction personnel.

The second reason of the building of the centric temples with 4 pillars and the raised supporting arches is the strengthening of the tower-like appearance which, as we have seen in Chapter 4, was the distinctive feature of Russian temples since Yury Dolgorukiy's times.

We should note that in Old Russian architecture the raised supporting arches in the crossing are also met incidentally in the temples with 6 pillars (Rostov cathedral of 1508-1512, the cathedral of Hutynsky monastery of 1515), but such construction in the conditions of 6 pillars (unlike 4 pillars) practically didn't influence neither the appearance, nor the interior of the temples. Therefore we don't refer them to the basic typological and construction features and, respectively, don't allocate to a separate type.

The temples of the second derivative type from the second basic type (digital marking – 2.2) are the temples with the corner wall supports. Four such Old Russian temples are known today: St. John Baptist church in Gorodishe (Kolomna), St. Nicholas church in the village of Kamenskoye of Naro-Fominsk subregion in Moscow region (Fig. 18; both temples – the beginning of the XIV century), and also the first cathedrals of Bobrenev and Golutvin monasteries, opened by the excavations (approximately the XV century)72.

Fig. 18. St. Nicholas church in Kamenskoye. Plan.

This type of temples is also not unprecedented: it, though in other architectural forms, existed in Byzantine provinces73. The similar scheme, when the drum stands on the corners of the walls, was realized also in the cathedral of Mirozhsky monastery (Fig. 19) and in St. George’s church in Old Ladoga (the end of the XII century).

Fig. 19. The cathedral of Mirozhsky monastery. Plan.

N.I. Brunov called such similar scheme of Byzantine churches "the naked cross" 74. B.L. Altshuller who together with M.H. Aleshkovsky possessed the honor of the first (though arguable in many respects75) systematic description of Old Russian temples with corner wall supports, applied the term "inserted cross" 76 to this scheme, having created the terminological сontamination with the classical definition of "inserted cross" as an almost full synonym of the cross-in-square system77. But B.L. Altshuller's definition most adequately reflects the bright expressiveness of the cross in the interior of the temple with the corner wall supports, therefore we will accept it.

It is important to note that Old Russian temples with corner wall supports are not of the cupola type, but of the cross-in-square type, and are a modification of the second main type of Old Russian temples – with 4 pillars, but the pillars were settled in the corner compartments and occupied them completely. This is proved by the following provisions:

– these temples accurately expressed cross-like plan both in the interior and in the ceiling;

– the cupola in such temples doesn’t cover the whole naos and that contradicts to the definition of cupola temples (see Chapter 2);

– in a number of such temples (the church in "Gorodishche" of Kolomna and the first cathedral of Old Golutvin monastery) the corner wall supports weren't united with the walls, i.e. they were pillars, not internal buttresses or anything else.

The purpose of replacement of the corner compartments with the supports was similar to the arrangement of the supporting arches raised by the steps: to increase the subcupola square. The drum weight is carried not by freely standing pillars, but by the walls – much steadier constructive element. There was an opportunity to increase the internal space of the temples without reliability decrease, and also without the use of more perfect construction technologies and more qualified personnel.

But Old Russian builders refused of the construction of the temples with corner wall supports very soon – in the XV century. Most likely, the increase of the subcupola square was not worth of the refusal of corner compartments.

The temples of the third derivative type from the second basic (digital marking – 2.3) are the temples with 4 pillars and pyramidally slanted walls and pillars. This construction technique is extremely rare both in Russia and in the world architecture, it was applied in Assumption cathedral in the “Gorodok” in Zvenigorod, the cathedral of Savvino-Storozhevsky monastery (both temples – the beginning of the XV century) and Trinity cathedral of Trinity-Sergius Lavra (1422-1423, Fig. 2078).

Fig. 20. Trinity cathedral of Trinity-Sergius Lavra. V. I. Baldin's reconstruction.

Earlier in Russia the similar technology was used only in the small church with 4 pillars in Perynsky monastery in Novgorod (about 1226).

We refer such temples to the separate derivative type and consider as the first typologically formed buildings two Zvenigorod cathedrals of the beginning of the XV century, since the construction of big stone church buildings with slanted walls and pillars represented the highest level of construction technology available only for the most qualified builders. The technology of construction of such temples essentially differs from the usual: here the alignment by a plumb doesn't suffice, the difficult system of adjustment of corners between the bases, walls, pillars, supporting arches and other arches is necessary.

In "pyramidal" temples of the XV century the level of construction technology we can see on the example that in the interior of Trinity cathedral of Trinity-Sergius Lavra the unique solution is realized: the slanted walls and pillars up to the height about 5 m are vertical, and then are "curved" inside. So they don’t "press" the people who are in the temple

The reasons of construction of such "pyramidal" temples seem the same as of the temples of the type 2.1 (with the raised supporting arches): firstly, strengthening of a tower-like appearance; secondly, increase of the internal space without reliability decrease. (Inclined walls create very steady "pyramidal" silhouette of the construction and actually are buttresses for themselves, providing the most uniform distribution of the loadings).

But, most likely, this technology was too difficult because the builders almost completely refused of it already at the construction of the cathedral of Andronikov Monastery (1425-1427)79 where the return to the first derivative type took place.

Later, the pyramidally slanted walls remained a rarity, the churches of Holy Spirit (1476) and of Presentation of Mary (1547) in Sergiev Posad had such walls (with much smaller degree of a pyramidality than in Trinity cathedral which served as the sample for these churches). Also Transfiguration cathedral in Solovki (1558-1566) had pyramidally slanted walls. Apparently, in the latter case the motivation of application of such construction technology was pragmatic: in this unique "fortress" temple enemy kernels were to ricochet from the walls (it is confirmed also by the exclusive thickness of the walls of the cathedral – up to 6 m, and by the pyramidal type of the towers of Solovki fortress with which the temple made the united fortification system)80. Typologically, Solovki cathedral with 2 pillars belongs to the third main type of temples (see Chapter 6).

6. The third main type of Old Russian temples

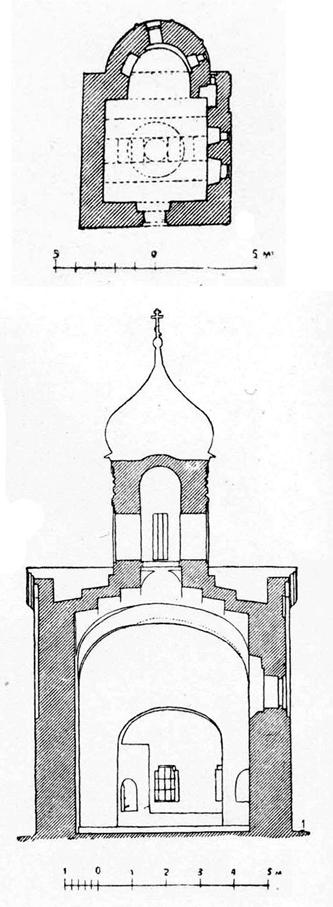

The temples of the third main type of Old Russian church architecture (digital marking – 3) are the temples with 2 pillars. Most likely, their construction was connected with the spread of high iconostases.

The time of high iconostases appearing in Russia is disputable and isn't the subject of our research81, but it is clear that in the XV century they were already widespread. About these iconostases, which covered the whole altar space of temples from the east pillars, N.F. Gulyanitsky fairly wrote: "Cross-in-square system, having lost the main branch of the cross in visual perception, in a certain degree lost also the symbolical sense, which had been visually materialized in hierarchically dismembered volume and spatial structure, in its difficult figurativity. Now the structure with 2 pillars, as resisting to the iconostasis plane, began to prevail more and more often" 82.

In other words, some Old Russian architects began to build temples with initial projecting of the high iconostases, thus the vast majority of temples was still constructed without planning of future high iconostases, i.e. more universally (the possible reason for it was that the formation of the full-fledged high iconostases could take very long time, and could be even never completed because of the lack of special icons).

The replacement of the couple of east pillars with the wall was the simplest and logical architectural concept of the system of 2 pillars: it increased constructive reliability of the temple without essential change of habitual centric structure, characteristic for the cross-in-square temples with 4 pillars. The first typologically formed temple of this type is Annunciation church in Blagoveschensky Pogost (the beginning of the XVI century, Fig. 2183).

Fig. 21. Annunciation church in Blagoveshchensky Pogost. Plan.

Respectively, we have the right to call the temples with 2 pillars the derivative type from the second main type (or "the degenerated second main type"), as these temples changed the number of the pillars from 4 to 2 under the influence of special circumstances. But as they formally ceased to be cross-in-square, we are obliged to allocate them into the separate main type (in our classification – the third).

There is one more reason of the reference of the temples with 2 pillars to the separate main type: for the first time the idea of initial construction of the temple with the high iconostasis (and, respectively, its "typological degeneration") was realized not in the temple with 4 pillars, but with 6 pillars, i.e. in the temple of the first main type. It is Moscow Assumption cathedral (1475–1479, Fig. 22).

Fig. 22. Assumption cathedral in Moscow Kremlin. Plan.

Solving the most difficult task of increasing of the internal volume of the temple, which his predecessors Krivtsov and Myshkin could not solve84, Aristotle Fioravanti for the first time in Russian architecture applied the one-brick cross-like vaults and the metal intra-armature. But his main engineering idea was the construction of additional arches behind the iconostasis. Thanks to it, the eastern part of the temple actually turned into the monolith and perceived the considerable part of the weight of the enormous drums. Respectively, there was an opportunity to build rather thin round pillars in the central and western parts of the cathedral, and that created the feeling of the lightness of the construction and of integrity ("hall-likeness") of the part of the naos intended for the praying people. Formally Assumption cathedral remained with 6 pillars, but actually it turned into the temple with 4 pillars, structurally expressed bema and "non-standard" arrangement of the heads.

St. Nicholas church in Nicolo-Uryupino (1664-1665), Nikitsky monastery cathedral in Moscow (1530-1540), Transfiguration cathedral in Solovki (1558-1566), a number of temples of the middle of the XVII century in Yaroslavl and many other belonged to the third main type.

It should be noted that in the temple in Nicolo-Uryupino, the architect Pavel Potekhin applied the "typological degeneration" not only to the system of 4 pillars, but also to the wall which replaced east pillars: on the place of this wall there was only the arch with the width of the whole quadrangle (Fig. 23), i.e. the part of a naos intended for praying people was expanded due to the full refusal of altar part of a quadrangle. The similar construction was realized also in Kazan church in Markovo (1672–1680).

Fig. 23. St. Nicholas church in Nicolo-Uryupino. Plan.

And in the XVI century the creative thought of Russian architects concerning the development of the temples with 2 pillars worked practically in the same direction which was set in due time by Aristotle Fioravanti: how to make the structure of the part of the naos, intended for praying people, more clear and integral. In this regard there was the type of temples which we can call derivative of the third basic: the temples with 2 pillars on the axis of the central drum (digital marking – 3.1).

The first typologically formed temple of this type is Annunciation cathedral in Solvychegodsk (1560-1579, Fig. 24). The builders of this temple refused of the eastern cross nave, the space of the naos intended for praying people gained its own symmetry on the axis "North-South", the quadrangle lost the centric character. In general, the cathedral typology significantly moved away from the cross-in-square prototypes with 4 pillars. According to G.N. Bocharov and V.P. Vygolov, "former, so-called "false 2 pillars system", which had formed in many respects by purely mechanical refusal of the eastern couple of columns, here for the first time conceded the place for the new decision in which 2 pillars system already acts as certain artly comprehended construction" 85.

Fig. 24. Annunciation cathedral in Solvychegodsk. The top part of the pillars and the light cut under the central drum.

Further the scheme with 2 pillars on the central axis "North-South" of subcupola space was applied in Lazarevsky church in Suzdal (1667), St. Nicholas church in Vologda (1669), Nativity cathedral of Solotcha monastery (1691), Trinity cathedral in Marchugovsky monastery (before 1698), Kazanskaya church in Toropets (1698), Resurrection cathedral in Derevyanitsky monastery in Novgorod (1700) and so forth.

7. The fourth main type of Old Russian temples

The temples of the fourth main type (digital marking – 4) are the pillarless temples covered by various systems of arches. This type has three subtypes.

The temples of the first subtype (digital marking – 4.1) have the pillarless quadrangle covered by the cross-like ceiling. (Formal definition of the cross-like ceiling: the closed vault with two crossing couples of additional arches and the opening for the drum in the center).

The researches conducted by the author in the beginning of the 2000th showed that the white stone Grand-ducal church of Trifon in Naprudnoe, covered by the brick cross-like ceiling (Fig. 25, 26), was built in the end of the XV century and is the first temple of this type known to us. The main arguments in favor of this position were the following86:

– the construction of the white stone temple far from stone quarries is more probable for the XV century than for the XVI century;

– in the case of construction in the XVI century, such temple as Trifon’s would have been too small and unpretendous for the significant Tsar's village Naprudnoe;

– only Trifon's church in Naprudnoe satisfies to all conditions of appearing at the turn of XV and XVI centuries of the cross-like ceiling arch, – the innovation which determined the "architectural fashion" for many decades ahead;

– on the basis of the analysis of Big Zion of Vladimir Assumption cathedral, the author specified that the construction of Trifon’s temple was most probable in the time interval from the middle of the 1470s till the middle of the 1480s.

Fig. 25. Trifon's church in Naprudnoe. Plan.

Fig. 26. Trifon's church in Naprudnoe. Cross-like ceiling.

The attempts of pillarless quadrangles building (and, respectively, of refuse of pillars which burden and shade naoses) were undertaken also before the end of the XV century – in Pskov. But these attempts conducted to essential reduction of the sizes of churches (the examples are many small temples covered by one arched vault, as the southern side-altar of church of Vasily on the Hill of 1413, or the arched vault with crossing additional arches as Nikita Gusyatnik’s church of 1470, Resurrection church in Pustoye of 1496).

The cross-like ceiling became the first successful attempt of pillarless covering of the rather big quadrangle. We will show it, having tracked its genesis.

If we just "take out" the pillars from the temple with 4 pillars, then above, except the vaults of the corner compartments, there will be two crossing arched vaults, each of which is cut through: from above – by the opening for the drum, longitudinally – by three couples of the arches (in the middle – by the supporting arches, on each side – by the arches over lateral naves). These arches will have nothing to be based on in the places where the footings of the supporting arches were based on the "taken-out" pillars earlier.

In this case the following constructive decision arises: to cut out in each of two crossing arched vaults not three longitudinal couples of arches, but one couple – at all length of the vaults. Then four points. in which supporting arches earlier leaned on the pillars, will "raise up" (Fig. 27), and the whole construction will base on the temple walls through longitudinal arches in the crossing arched vaults. In this case not only the pillars disappear, but also the supporting arches (Fig. 28). Optimum depth of cutting gines the chance to build not only a reliable cross-shaped construction of the crossing arched vaults, but also to make smooth transition from the crossing points to the corner compartments.

Fig. 27. Conditional scheme of "cutting out" of the pillars and "raising up" of the footings of the supporting arches.

Fig. 28. The conditional scheme of the replacement of three couples of the arches with one couple at all length of the temple (preserving the former proportions).

As a result, the unique ceiling was invented and became known as the cross-like. The author showed in special research87 that no direct or indirect analogs of this remarkable architectural concept existed anywhere in the world, and the cross-like ceiling was invented in Ancient Russia (more precisely – in Moscow grand duchy) without any loans or influences.

We see that the temples with the cross-like ceiling came from the second main type of Old Russian temples – the cross-in-square centric temples with 4 pillars. But since pillarless temples aren't cross-in-square by definition, we are obliged to refer them to the separate main type (in our classification – the fourth).

The temples with the cross-like ceiling were built in a large number in the XVI century, mainly in Moscow region (the church of Conception of Anna "in the Corner" in Kitay-gorod, before 1493; the church of Nativity in Yurkino, before 1504; Nikita Martyr’s church beyond the Yauza, the 1530s, reconstructed in 1595; Old cathedral of Donskoy monastery, 1591-1593; etc.) 88. The similar ceilings, though in significantly transformed look, were sometimes built also in the XVII century (an example – Vvedensky cathedral in Solvychegodsk, 1688).

The temples of second subtype of the fourth main type (digital marking – 4.2) are pillarless temples with systems of the vaults of "Pskov" type. We have spoken above about the simplest options of this subtype as about the first attempts of covering the pillarless quadrangles. In the middle of the XVI century, the "Pskov" system reached the typological completeness: the construction of the temples covered by the system of the arches leaning at each other started. (Other version of the name of this type – the system of the step arches, but here the terminological сontamination with type 2.1 is possible).

It is possible to consider the church of Assumption in Gdov (1557-1561, Fig. 29) 89 as the first temple of type 4.2.

Fig. 29. Church of Assumption in Gdov. Plan and section.

Such type of the ceiling, though allowed to cover quadrangles, comparable by the size to the quadrangles of the temples with the cross-like ceiling, didn't possess clarity and harmony of the cross-like ceiling. In this regard the type 4.2 remained the local Pskov phenomenon though its echoes sometimes got the response in architecture of the XVII century (an example – Nikon’s church in Trinity-Sergius Lavra, constructed in 1548, reconstructed in 162390).

And the cross-like ceiling, though was a simple, clear and reliable construction, but in the progress of construction technology in the XVII century everywhere gave way to more simple, clear and reliable system – the closed vault.

Formally speaking, the closed vault is formed from the cross-like ceiling, "cleaned" of the additional arches. But as we have no confidence that actually the closed vault came from the cross-like ceiling, and wasn't a self-sufficient invention prepared by the development of construction technology (the latter at the accurate and clear form of the closed vault seems more probable), we consider the temples with the closed vault not derivative type from the type 4.1, but the third subtype of the fourth main type (digital marking – 4.3).

As Vl.V. Sedov showed, the first closed vaults were built in the 1550s in a number of Novgorod temples (refectory churches of Varlaam Hutynsky in Hutynsky monastery, 1550-1552, of Annunciation in Mikhail street, the 1550s), and a little bit later the closed vault in the cathedral of Rizopolozhensky monastery in Suzdal91 was built.

In the XVII century the closed vault was the dominating ceiling of the pillarless temples, it was used in such architectural masterpieces as churches of Trinity in Nikitniki (1630-1650s), Virgin's Nativity in Putinki (1649-1652), Resurrection in Kadashi (1687-1695) and many others.

Fig. 30. Church of Transfiguration in Nikolskoye village in Yaroslavl region (1700). Closed vault.

8. The fifth main type of Old Russian temples

The questions of the origin of Old Russian hipped-roof architecture (construction of temples with the hipped roofs over the naoses) are in details considered in special researches of the author92. Here it makes sense to stop briefly on some provisions important for understanding of its typological formation and classification.

The researchers are occupied with the questions of the origin of hipped-roof architecture not for the first hundred of years. As the detailed historical review of all points of view is beyond our research, we will list only the main ones (in the chronological order of their appearing):

– hipped-roof architecture of Ancient Russia occurred from late West European Gothic93;

– hipped-roof architecture was created on the basis of Old Russian wooden architecture94;

– hipped-roof architecture occurred from Old Russian and Serbian temples with raised supporting arches95;

– hipped-roof architecture has Eastern origin96;

– hipped-roof architecture was created under the influence of architecture of the towers of Old Russian fortresses97;

– formation of hipped-roof architecture was influenced by Old Russian churches-belltowers98;

– Old Russian hipped roofs were "an accident in architecture" and just replaced the cupolas covering naoses99;

– hipped-roof architecture of Ancient Russia occurred from Romanesque100.

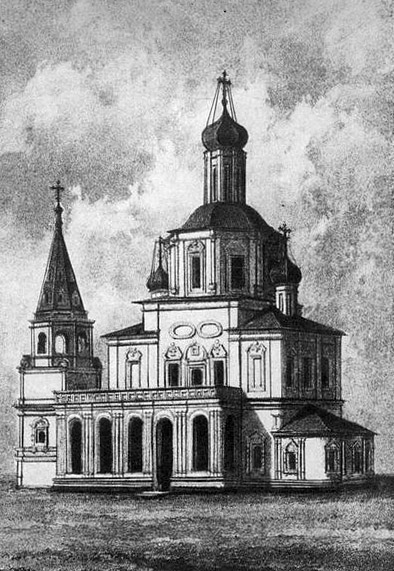

Before considering the above-mentioned points of view, we will remember that the architectural and archaeological researches of V.V. Kavelmakher (1980-90s)101 and of the author of this research (2000s)102 showed that hipped-roof Trinity (nowadays Intercession; we will further call it Trinity without reservations) church in Aleksandrovskaya Sloboda (Fig. 31103) was constructed in 1510s and, respectively, was the first Old Russian hipped-roof temple. The author also showed that Aleviz Novy104 was the architect who built this temple. Earlier the church of Ascension in Kolomenskoye (1529-1532, the probable architect was Italian Petrok Maly105) was considered as the first hipped-roof temple.

Fig. 31. Trinity church in Aleksandrovskaya Sloboda. Section by the line West-East. Reconstruction by V.V. Kavelmakher.

We will begin the research of probable sources of Old Russian hipped-roof architecture with West European Gothic. During the forming of Old Russian architecture of the XII-XV centuries, "tendency upwards" constantly amplified in it. The general "high-rise" proportions of temples (see Chapter 4), the appearing of the raised supporting arches (see Chapter 5), the covering of the pedestals of the drums by decorative keel-like arches (“kokoshniks”), the construction of high onion domes over the cupolas106, the construction of the tower-like churches "under the bells" 107, – all these phenomenons correspond to the general impression of the image of Gothic.

But it is only the general impression. By more fixed comparison we are compelled to deny the origin of Old Russian hipped-roof architecture from West European Gothic.

Firstly, as we have shown in Chapter 4, the tower-like appearance of the main volume of the temple is uncharacteristic for Gothic architecture.

Secondly, the covering of the naos by a hipped roof is also uncharacteristic for West European Gothic. The crossings were sometimes covered by wooden hipped roofs (an example – Gothic church of Virgin Mary in Bruges, Fig. 32), but we don't know any stone hipped roof neither over a naos, nor over a crossing in any big and significant Gothic temple. In a mass, the hipped-roof form was used in Gothic Europe only for the towers.

Fig. 32. Church of Virgin Mary in Bruges.

Thirdly, one of the most characteristic tendencies of Gothic is the increase of the internal space of the temples. This tendency found reflection in Old Russian architecture: pillars became thinner and thinner, less and less temples had internal lisens, pillarless temples with corner wall supports appeared (see Chapter 5), then the temples with cross-like ceilings (see Chapter 7). For example, S.S. Podjyapolsky fairly referred Assumption cathedral of Aristotle Fioravanti to the type of Gothic "hall church" 108. But the situation with hipped-roof architecture is opposite: in comparison with co-scale cross-in-square churches and furthermore with West European basilicas, the square of the naoses of hipped-roof temples is small.