To the page “Scientific works”

S. V. Zagraevsky

Forms

of the domes of the ancient Russian temples

Published in Russian: Çàãðàåâñêèé Ñ.Â. Ôîðìû ãëàâ (êóïîëüíûõ ïîêðûòèé) äðåâíåðóññêèõ õðàìîâ. Ì.:

Àëåâ-Â, 2008. ISBN 5-94025-096-3. Earlier the theses of the article were

published in Russian: Çàãðàåâñêèé Ñ.Â. Ôîðìû ãëàâ (êóïîëüíûõ ïîêðûòèé) äðåâíåðóññêèõ õðàìîâ.  êí.: Ìàòåðèàëû îáëàñòíîé êðàåâåä÷åñêîé êîíôåðåíöèè

(14 àïðåëÿ

Annotation

Professor S.V. Zagraevsky’s research is devoted to the

forms of the domes of the temples of Ancient Russia. Basing on the

analysis of ancient images, architectural and archaeological data and general

trends of Russian and world architecture, he showed that the onion (bulbous)

domes were invented in

I

General terms

First of all, it is necessary to define what we call the domes of

temples. Encyclopedias and manuals1 sometimes define them as

synonyms of cupolas, sometimes as decorative coatings of cupola vaults,

arranged on drums. It is known that domes can be onion (bulbous), helmet,

pear-shaped, umbrella-shaped, conical, etc. Cupolas or cupola coatings,

arranged not on light, but on decorative (deaf) drums, are also called domes.

We shall define the cupolas only as cupola vaults, and the domes as

decorative cupola coatings, although in the context of our study this

definition requires considerable refinement, associated with the understanding

of the helmet domes. So the special form of cupola coatings, close to the

ancient form of helmet, is called. Such conclusion we see today on the natural

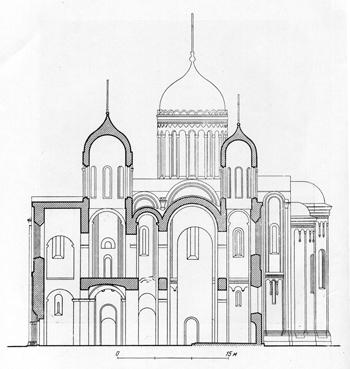

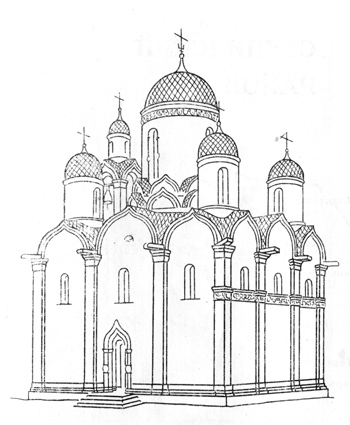

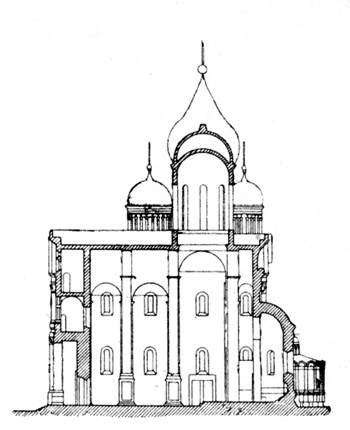

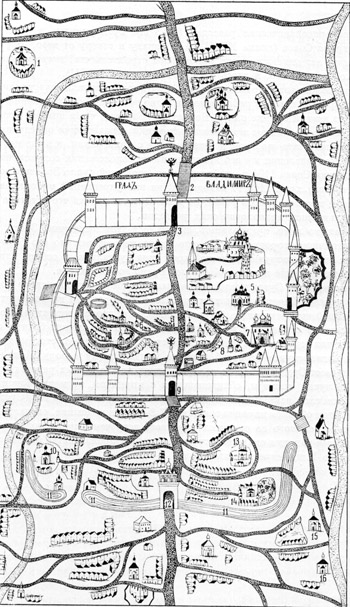

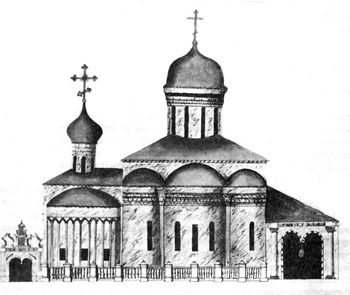

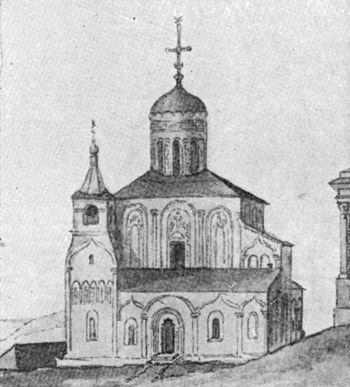

and the "paper" reconstructions of pre-Mongolian cathedrals of

Vladimir-Suzdal land (Fig. 12) and of the vast majority of churches

and cathedrals of XV-XVI centuries (Fig. 23).

Fig. 1. Assumption Cathedral in

Fig. 2.

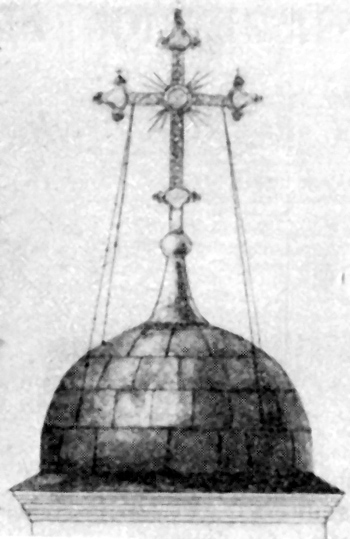

But a dome of a temple is a segment of a sphere

corresponding to the form of a helmet only at the edges. Accordingly, in order

to create a helmet design, it is necessary to arrange a wooden, metal or brick

construction on the cupola vault. Then, an under-cross stone, with the hole,

where the cross is inserted, is put on the dome or on this construction. Then

all this is covered by roofing materials (iron, lead, copper, tile, etc.).

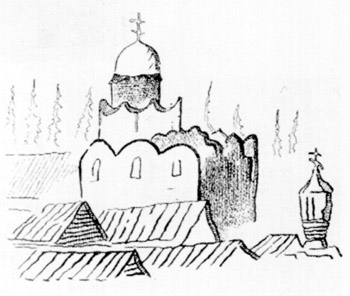

Thus, the helmet dome is very different from a simple

cupola coating by roofing material directly on the vault. And even if an

under-cross stone is placed in the center of the simplest cupola coating, the

form of dome may be close to the helmet only in the case of a very small dome

(Fig. 34). In the case of a large dome, an under-cross stone, coated

by roofing material, will look like a little ledge on the cupola coating.

Fig. 3. Dome of the

Hence, we must distinguish the simple cupola coating

and the helmet dome. In connection with this we must specify that we are

talking about domes in general, which can be either simple cupola coatings

(with a projection in the middle if there is an under-cross stone), or have

helmet, onion (also called bulbous; further we shall call them only onion),

pear-shape or any other form.

Let us also define the difference between the helmet

and onion domes: the latter also have keel-like top, but the maximum diameter

of the dome is larger than the diameter of the drum, i.e. a visual

"barreling" is present. The height of onion domes is usually not less

than their width. The height of the helmet domes is always less than their

width.

Pear-shaped domes are characteristic for “Ukrainian

Baroque”, umbrella-like and conic – for Transcaucasian architecture. In ancient

Russian architecture and in the relevant iconography they were practically

absent (see Chapter 2). The main theme of our research is the genesis and the

quantitative ratio of such types of domes as simple cupola coatings, helmet and

onion.

We should view primarily not the positions of

individual researchers, but stereotypes, settled in XIX century. Let us

enumerate them:

– "Byzantine" simple cupola coatings

occurred in the most of the principalities of pre-Mongol Rus (Kiev, Chernigov,

Smolensk, etc.);

– helmet domes prevailed in pre-Mongol Vladimir-Suzdal

principality. Then this form of the domes took place in Tver and Moscow grand

duchies, and then in centralized Russian state. Accordingly, the vast majority

of Russian churches of XIV-XVI centuries are generally reconstructed with

helmet completions;

– onion domes appeared (occasionally) in the second

half of XVI century, and in the XVII century they became a mass phenomenon.

According to those stereotypes, the following view on

the genesis of the dome forms took place: simple cupola coating was borrowed

from Byzantium, then it “stretched up” more and more (as well as the

proportions of the temples themselves) and transformed into a helmet. Then,

once in the XVI century hipped architecture appeared, the altitude of helmet

domes proved insufficient, and onion-form structures started to be built on the

cupolas5.

B.A.Rybakov was the first to disagree with those

stereotypes. In the mid of 1940s he, considering after D.V.Aynalov and

A.V.Artsikhovsky that many miniatures of Radzivil Chronicle of XV century are

the copies of the images of XII-XIII centuries, suggested that onion domes,

portrayed on these miniatures (see Section 4 of the statistical illustrative

material) appeared in the reality in the end of XIII century6. In

1950s this position of B.A.Rybakov was supported by N.N.Voronin7.

However, strangely enough, those observations by

B.A.Rybakov and N.N.Voronin received no resonance in the scientific world.

Perhaps the negative role was played by uncertainty of their conclusions, and

also because in future their researches on genesis of the onion domes were not

developed: apparently they considered their observations as local. For example,

onion domes could appear in the end of XIII century, but not everywhere and

only in wooden architecture, and in the end of XVI century the construction of

such domes on stone temples could begin8. Thus, there were no

apparent contradictions with the stereotyped position.

In the end of twentieth century A.M.Lidov turned to

the problems of genesis of the onion domes9. Having advanced in his

article some considerations about the origin of the onion domes (the analysis

of these considerations we will hold in Chapters 2 and 4), the researcher still

kept to the stereotyped views on the appearing of this form of the domes in the

turn of XVI-XVII centuries, arguing that dating by the fact that onion domes

before the turn of XVI and XVII centuries were not preserved to our time10.

I.A.Bondarenko, who also devoted a special article to

the origin of the onion domes11 (the point of view of this

researcher on the prototype of these domes will be discussed in Chapter 4),

noted that there is no need to insist after A.M.Lidov on the late origin of

onion forms of the domes only on the ground that we have no surviving monuments

of such domes, reliably dated before XVI century. We must agree with

I.A.Bondarenko and just clarify: since ancient Russian onion domes are

decorative coatings, based on wooden carcasses, then the situation is typical

for the history of ancient wooden architecture: the lack of architectural and

archaeological information about the onion domes before XVII century can not be

the information about the absence of such domes in reality.

I.A.Bondarenko suggested in the same article

(unfortunately, without a reference to the similar position of B.A.Rybakov and

N.N.Voronin) that "the fact that the onion shape of the domes was used in

early Moscow “Zions”, censers, miniatures and carved icons from the XIII

century (what A.M.Lidov also notes), gives evidence that this form was known,

had a sacred significance, and therefore could, and even, perhaps, should have

been used in architecture”12. But the researcher confirmed his

position by no concrete evidence and expressed no substantive assumptions about

the time of occurrence of such domes.

As a result, the assumption of I.A.Bondarenko about

relatively early origin of the ancient onion domes was expressed in an equally

controversial and unexamined form, as the similar position of B.A.Rybakov and

N.N.Voronin, and, accordingly, received no resonance in the scientific world

and in popular literature.

Thus, to date, all textbooks, reference books,

scholarly and popular works on history of ancient architecture straightly

(literally) or indirectly (in the form of reconstructions of the temples)

reproduce the stereotypes of XIX century, and no researcher attempted to refute

them directly.

In this regard, we have to re-consider the genesis of

the onion domes with the involvement of all possible set of sources.

II

Analysis

of iconographic sources

To examine the genesis of the onion domes, we analyzed

architectural iconographic sources – ancient Russian icons, miniatures and

plans. Full coverage of iconography of temple architecture is impossible, but

we sited enough representative sources (totally 147), allowing a statistical

analysis. Statistical illustrative material is contained in the Appendix.

In accordance with the collected statistics on ancient

Russian icons, frescoes, miniatures and works of decorative art (hereinafter we

shall collectively call them images) of XI-early XVII century (see Sections 1-7

of Appendix), the onion domes are shown in the following proportions relative

to other dome types:

– images of pre-Mongolian time: 18%;

– images of the second half of XIII century: 100%;

– images of XIV century: 82%;

– images of XV century: 84%;

– images of XVI century: 94%;

– images of the turn of XVI and XVII centuries: 100%.

Analyzing these results, first of all we must be aware

that Old Russian images were mostly oriented to Byzantine models13,

and iconography usually passed from century to century. Hence, the simple

cupola coatings in ancient Russian images could be a tradition of Byzantine

icon painting, but the onion domes in the images had to have some

"own" models.

Possible models of depicted temples with onion domes

may be reduced to two basic ones: either some "model" image or the

real onion domes on the real churches.

A.M.Lidov believed14 that the Old Russian

artists used as the model an image of Jerusalem Edicule (Chapel inside Holy

Sepulchre), where there was a hypothetical "dome" of onion form in XI

century15 (Fig. 416).

Fig. 4. "Dome" of

But we can not accept the assumption that the model

for the ancient artists, who reproduced the onion domes in large numbers, could

be any image (of Edicule, or of another real or imaginary building – such as

Rock Mosque, as I.A.Bondarenko thought, whose position we shall consider in

Chapter 4). The reasons are following.

First, we have no assurance that Jerusalem Edicule had

an onion-shape top since XI century. The earliest surviving image of a medieval

completion of Edicule is approximately dated by XIV century, and it is highly

conditional and inaccurate image with general trend of "flattening"

of the lower parts of the objects17 (Fig. 5). On all subsequent

historical images, starting from XV century18 (Fig. 6), the

completion of Edicule has the form of helmet (and more Western European helmet

than Russian). The existing onion top (see Fig. 4) of Edicule was built in the

new time.

Fig. 5. Image of Edicule, stored in

Fig. 6.

Secondly, the "dome" on Jerusalem Edicule is

not a dome in the understanding of a decorative coating above the cupola (see

Chapter 1). That is the "cap" over the hole for extraction of candle

smoke and fumes from the people’s breathing19.

Thirdly, Edicule is a small part of Holy Sepulchre,

and not a church, but a chapel. If the temple itself had an onion dome, it

could at least be argued to be taken as a model of images. But the adoption of

a small interior chapel (even if it had an onion top) as a model for the huge

number of images of the largest ancient Russian cathedrals and churches is very

unlikely.

Fourthly, there is no cross on Edicule, and it is

unlikely that there could be a cross in ancient times, as the only figure,

which depicts a cross (see Fig. 5), as we have shown above, is very

conventional. The absence of the cross on Edicule is quite natural: we have

shown the "utilitarian" nature of its “dome”, moreover, it is

unlikely that a cross in Jerusalem temple was located above Edicule, but not

over Calvary. And on ancient Russian images we see the domes with the crosses.

Fifthly, I.A.Bondarenko believes that not Edicule, but

Jerusalem Rock Mosque (which the Crusaders called “Holy of Holies”) was a

possible prototype of the Russian onion domes20. But in Chapter 4 we

shall show that the dome of that temple did not have onion shape.

Sixth, the temples of Jerusalem in the era of the

Crusades of XI-XIII centuries were well known in Western Europe and Byzantium.

But we do not see there mass images of churches with onion domes neither at

that time, nor since.

Seventh, the temples of Ancient Russia, though with

high artistic convention, but were painted of nature (arched gables, windows,

hips, apses, cornices, decor, crosses above the domes are reproduced), but the

shape of the domes, according to stereotyped positions, for some reason were

provided fictitious. It is also very unlikely.

Eighth, if Ancient Russian temples had been reproduced

of the images almost identically (by some single "model"), we could

have talked about some "model" image for the domes. However, the

churches are drawn extremely diverse and, as we have seen, quite realistic;

Ninth, the onion domes in the beginning of XIV century

were represented not only by Moscow, Tver and Novgorod artists. We see such

dome at the icon of Kiev school (see Fig. C-8, C-9; the letter "C" in

the figure means that it belongs to the statistical illustrative material). So,

at this time the images of onion domes were already widespread in Ancient

Russia. It is impossible to imagine that because of some "model"

image the Byzantine tradition of reflection of the simple cupola coatings on

the icons, frescoes and miniatures was revised.

Thus, for the ancient artists, who reproduced the

onion domes in architectural iconography in large numbers, no images could be

models.

Consequently, the only option remains: – the onion

domes on the real temples of Ancient Russia served as a model for the artists.

Form of the domes could be interpreted by the artists

rather freely, but within the overall onion forms that existed in reality. In this connection it is appropriate to recall the

words of I.A.Bondarenko: “In the Middle Ages there were no strict bounds

between visual, applied arts and architecture, especially when we talk about

the problems of semantics and symbols forming”21.

Let us look if some wooden temples could be the models

for the ancient images of the onion domes.

Perhaps if we had been talking about icons from

villages and small towns, small local churches could have served as the models

for them. But the vast majority of images, shown

in the statistics, are the icons and frescoes of Moscow, Novgorod and Pskov

schools, originating from the large stone temples. Accordingly, the artists

were to orientate to large cathedrals, not to minor churches.

Let us note that N.N.Voronin attracted

“Great Zion” of Assumption Cathedral in Vladimir (Fig. C-22), the top of which

(the work of Moscow artists) is dated by 1486, for his reconstructions of

St.George's Cathedral in Juriev-Polsky22 and the first Assumption

Cathedral in Moscow23. Researcher believed that the completion of

Zion corresponds with the hypothetical original completion of these temples.

This position is quite controversial (it is more likely that the completion of

Zion reproduces the completion of the contemporary temples of the late XV

century – in particular, the churches of Trifon in Naprudnoe and Conception of

Anna in Kitay-Gorod24), but there is no doubt about the validity of

the method of Zion usage for the reconstruction of the unpreserved cathedrals. In this regard, we must note that the

onion dome of this Zion reproduced the reality of the end of XV century (and

possibly of even earlier time).

The earliest images of the onion domes are found in

Galicia-Volhynia miniatures of 1164 (see Fig. C-3). But we can not assume that

in pre-Mongolian time this form of domes could be widely distributed: there are

no more known images (and, consequently, statistical data), and the hypothesis

of D.V.Aynalov, A.V.Artsikhovsky and B.A.Rybakov’s hypothesis that the

miniatures of Radzivil Chronicle of XV century are replicas of pre-Mongolian

images (see Chapter 1 and Fig. C-18), is still only a hypothesis. So the

availability of such domes in pre-Mongolian time is not proved.

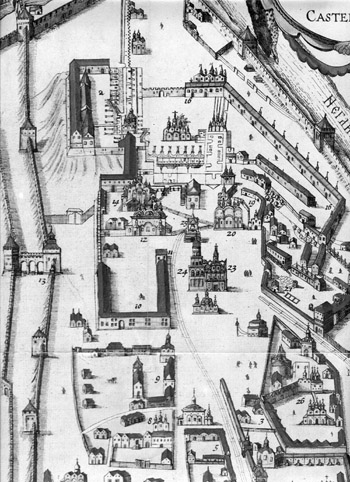

The statistics shows that the vast majority of temples

had the onion domes since the second half of XIII century. And though in the

iconography of XIV-XVI centuries sometimes (although rarely) other types of the

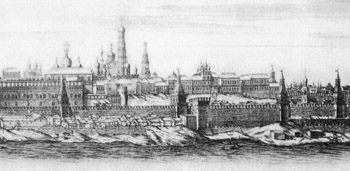

domes occur, the plans of Moscow of the turn of XVI and XVII centuries (see

Section 6 of the statistical illustrative material) clearly indicate that at

this time the domes were exclusively of onion form. This is confirmed also by

the images of other Russian cities (see Section 7 of the statistical image

material).

It is important to pay attention to the images from

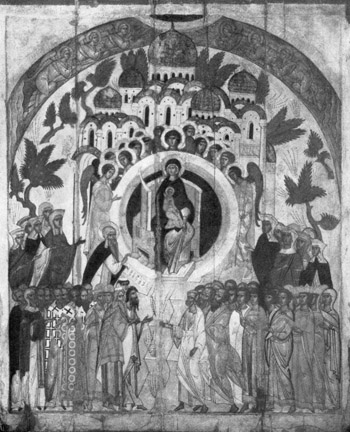

the manuscript of Hamartolas (see Fig. C-4). In 1294, the generalized “Image of

Church” was shown with the onion dome. So, at

this time, as the statistics also confirms, the onion domes were built on the

temples not occasionally, but mostly.

As we have noted, the onion domes

were represented in the beginning of XIV century not only by the artists of

Moscow, Tver and Novgorod. This type of domes we see

on the icon of Kiev school. This again confirms that onion domes at the turn of

XIII-XIV centuries occurred everywhere.

All domes, built above the hipped

roofs in XVI century, were also onion-formed (see Section 5 and 6 of the

statistical illustrative material).

In theory, the simple cupola coatings

of pre-Mongolian time could exist on some minor temples long enough, but there

is no doubt that by the end of XVI century they were everywhere replaced by the

onion domes (we see only the onion domes on the plans and panoramas of the turn

of XVI and XVII centuries).

It is important to note that we see no helmet domes

neither in pre-Mongolian, nor in early post-Mongolian time. The first image, which presents the dome form, close

to a helmet, appeared at the turn of XV and XVI centuries (Sections 4 and 5 of

the statistical illustrative material). However, these images can not testify

that in this time churches had helmet domes in reality: it is clear that this

form of dome is shown only on the large central cupola, and if the latter had

been drawn with an onion dome (as the small domes), then they would not have

fitted into the respective images.

All other – "non-onion" –

forms of cupola coatings (umbrella, conical, etc.) are portrayed so rarely that

we can consider them as an artistic styling. This

position is based not only on the data of iconography, but also on the

techniques of construction: for the erection of any coating, except the

simplest, the construction of a wooden or metal frame on the cupola is

required. Consequently, it was easier and more logical for the builders to

create domes of the mass (onion) form, than of any other.

Conclusions about the absence (at

least, negligible distribution) of helmet, umbrella, conical and other

"non-onion" dome forms in XIV-XVI centuries can be also confirmed by

one more important fact, which we have already mentioned: on the plans and

panoramas of the turn of XVI and XVII centuries we see

only the onion domes. Consequently, if in

XIV-XVI centuries the domes of

"non-onion" form could theoretically occur, then only

sporadically, and at the first opportunity they were replaced by commonly used

onion domes25.

The question, when the helmet domes

appeared in Russian architecture, we shall discuss in details in Chapter 5.

III

Onion

domes and fires

It may seem strange that almost

universal transition from the simple cupola coatings to the onion domes could

occur so quickly – within a few decades of XIII century. But in fact, there is nothing strange: the domes of the temples were

rebuilt very often, and the fires were the main reason.

Here is a very comprehensive and

informative quote from Sergei Soloviev: "Chronicle mention the fires in

And though the stone temples usually (though not

always) stood the fires, the wooden skeletons of their domes and roofs were

easily burnt. For example, on the limestone

arches of Assumption Cathedral in Vladimir the fire melted metal was found27,

in 1493 a fire lit wooden construction under the roof of the cathedral28,

in 1536 in Vladimir half of the roof of Assumption Cathedral was burnt29

and also the entire roof of Demetrius Cathedral30, in 1547 the dome

of Assumption Cathedral was burnt31, in 1394 – the dome of

St.Sofia in Novgorod32, in 1628 – the

dome of Trinity Cathedral in Troitse-Sergiev33. Such examples are

numerous.

Let us note that the technical

problems with the construction of new onion domes did not arise, because the

installation of a wooden frame on the dome is the work not for stone craftsmen,

but for carpenters, and there we always enough carpenters in Russia.

IV

Genesis

of the onion domes

The questions of genesis of the onion domes were

studied very poorly even within the stereotypes relating to their appearance at

the turn of XVI and XVII centuries34. Now, when we have shown that

those domes occurred everywhere in Russia already in the end of XIII century,

their genesis becomes even less clear. But we can still make some observations.

First, we should note a low probability that the onion

domes of ancient stone temples were taken from wooden architecture. The form of

those domes is complex, sophisticated, “aristocratic”, and therefore they could

hardly have appeared firstly on wooden churches (and even on minor stone

temples).

Let us not forget about the rapid (within a few

decades) distribution of the onion domes. Wooden churches, as well as the minor

stone temples, could hardly be "setters" of the trend, which

disseminated so quickly and widely.

Borrowing of onion form of the domes of ancient

Russian temples from Muslim world35 seems more than doubtful. In XV

century the form of stone domes, close to the onion, widespread in the East

(Gur-e Amir in Samarkand, the beginning of XV century, Fig. 7; Kalyan Mosque in

Bukhara, XV century; Mausoleum of Kazi-Zade-Rumi in Samarkand, 1430s; etc.),

and within the stereotype, relating to the appearance of the onion domes in

Russia in the end of XVI century, "oriental influences" could be at

least argued. But since, as we have shown in Chapter 2, the onion domes in

Fig. 7. Gur-e Amir in

We know some isolated examples of early Muslim stone

domes, which shape is visually close to the onion form (Dome of the Rock in

Jerusalem, VII century, Fig. 8; Sidi Okba Mosque in Kairouan, Tunisia, X

century, Mausoleum of Al-Shafiya in Cairo, 1212; the mausoleums of XI-XII

centuries in Aswan, etc.) In particular, I.A.Bondarenko attracted Rock Mosque,

which the Crusaders called the “

Fig. 8. Dome of Rock Mosque in

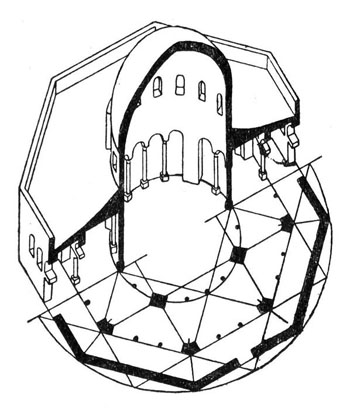

But such domes can be called onion neither formally

nor in fact: that are high cupola vaults, which are the continuations of the

drums (Fig. 937). The upper parts of these vaults have no keeled

bending, which are characteristic for

the ancient Russian onion domes. Their visual "onion" effect is

created previously by the spreading of the tops of the drums by the cupolas and

by the difference in color between the cupola coating and the drums lining (for

example, a bright, shiny and uniform color of cupola coating of Rock Mosque

visually increases it, comparing with a dull ornamented drum – see Fig. 8).

Fig. 9. Rock Mosque in Jerusalem.

Axonometry.

For this reason we can not recognize the impact of the

dome of Rock Mosque (and of other early temples with similar domes) on the

origin of the onion domes of Old Russia, where we see no transition: already in

XIII century, since the appearance of these domes, they had their own,

absolutely unique shape, characterized by keeled top and significantly bigger

diameter of the domes, comparing to the diameter of the drums (see Section 2 of

the statistical illustrative material, Fig. C-4, C-5, C-6). These basic

features of ancient Russian onion domes are absent in Rock Mosque.

In Western Europe there were also no onion domes in

XIII century (the earliest example, which the author of this study knows, is

the completion of the towers of Frauenkirche in Munich, the end of XV century,

Fig. 10).

Fig. 10. Towers of Frauenkirche in Munich.

End of XV century.

Jerusalem Edicule also could not become a model not

only for the ancient artists, who depicted large numbers of onion domes on the

icons, frescoes and miniatures (as we have shown in Chapter 2), but also for

the ancient builders, who started in XIII century to build onion domes on the

churches en masse. The reason for this is practically the same as discussed in

Chapter 2:

– the "dome" on Jerusalem Edicule, even if

it had the onion form (what, as we have seen in Section 2, is very doubtful) is

not a dome in the understanding of a decorative coating above the cupola (see

Chapter 1). That is the "cap" over the hole for extraction of candle

smoke and fumes from people’s breathing;

– Edicule is a small part of Holy Sepulchre, and not a

church, but a chapel. If the temple itself had an onion dome, it could at least

be argued to be taken as a model for the builders. But the adoption of a small

interior chapel (even if it had an onion top) as a model of the huge number of

the onion domes of the largest ancient cathedrals and churches is very

unlikely;

– temples of Jerusalem in the era of the Crusades of

XI-XIII centuries were well known in Western Europe and Byzantium. But we do

not see there mass onion domes on the churches neither at that time, nor since.

Thus, we must assume that even if somewhere else in

the world before XIII century there had been occasionally erected onion-shape

domes or cupola vaults, they firstly appeared in large numbers in Ancient

Russia. Moreover, widespread occurrence of onion shape of cupolas in Muslim

East in XV century could take place due to influence of Russian architecture.

Let us try to find an explanation for the fact of mass

occurrence in Russia of "built-over" domes in the second half of XIII

century.

Firstly, we should note that it was not necessary to

sharpen the domes so they did not accumulate snow and stagnate water: if such a

need had occurred, then something similar was built already in XIII century

over arched gable vaults, where the problem of accumulation of snow and water

was even more acute.

It was not necessary also to warm the temples by the

erection of the decorative structures above the cupolas (so that those domes

played the role of heat-insulating "attics"): in Ancient Russia the

vast majority of stone churches and cathedrals were "cold" (i.e.,

unheated), and service was not conducted there in winter.

There are other, far more grounded, considerations on

the causes of building of the carcasses above the cupolas of ancient Russian

temples.

First, during pre-Mongolian time we see the

"pulling up" of church buildings. For example, G.K.Wagner wrote that

the churches of "tower-like" type had a dynamic striving upward, and

it is possible that if the development of “altitude” architecture had not been

interrupted by Mongol invasion, then Russia would have known something like

Gothic38. And when the constructive possibilities of altitude

reaching (higher arches and drums) were exhausted, the additional

"towering" was achieved through wooden superstructures above the

cupolas.

Second, the size of the crosses steadily increased in

Russia until XVII century, and they were gradually transformed from the "Byzantine"

type (the simplest form) to the "classic" Old Russian type, which we

now see on the temples (large, ornamented, of complex shape). Accordingly, the

problem of reliability of crosses installation also increased.

The chains, holding the cross, we see for the first

time only in 1536 on the icon “Vision of Sacristan Taras” (see Fig. C-25). Of

course, such chains, not reflected in iconography, could have appeared earlier,

but hardly in XIII-XIV centuries. And it was impossible to install a large cross

into the hole in the under-cross stone without additional pairs – it would have

been broken by any strong wind.

This problem was solved by quite rational design of

the carcasses above the cupolas: the cross had a long lower bar (a

"mast"39), which pierced the carcass from top to bottom

(thus, was fixed firmly) and was inserted into the hole in the under-cross

stone.

Third, during the Mongol yoke the domes were rarely

covered by metal: there were no economic possibilities. And it is easier to

cover with “lemekh” (wooden tile) a wooden carcass, which can be sewed by

boards, than a stone vault.

All the above mentioned considerations explain the

appearance of high wooden carcasses on the cupolas, but do not explain the

onion shape of these carcasses. Why was the diameter of the dome larger than

the diameter of the drum? Why did the carcass receive the complex onion form,

but not the maximum sustainable direct form? Umbrella or cone-shaped domes

could give the temples the same altitude, strengthen the crosses and be coated

with tile also effectively, be much simpler and more reliable in construction

and operation.

Researchers attempted to explain the origin of the

onion domes by their symbolic.

Some of those explanations lie outside the view of

Orthodox religion. Thus, S.D.Sulimenko saw in the form of the onion domes a

"solar window", which was a canonization of the images of solar light

in Vedic mythology and architecture of Buddhist temples40.

N.L.Pavlov saw in these domes the form of a "world egg" – an archaic

image of the Universe41.

But the author of this study had to write more than

once, that all architectural features of churches were necessarily confirmed by

Russian Orthodox Church, which in any case would not have allowed any direct

Pagan, Buddhist, Muslim or other influence42.

In the bounds of Orthodoxy, E.N.Trubetskoy tried to

solve the problem of symbolism of the onion domes. He wrote: "The

Byzantine cupola above the church represents the vault of heaven above the

earth. On the other hand, the Gothic spire expresses unbridled vertical thrust,

which rises huge masses of stone to the sky. In contrast to these, our native

onion dome may be likened to a tongue of fire, crowned by a cross and tapering

towards a cross. When we look at the Ivan the Great Bell Tower, we seem to see

a gigantic candle burning above Moscow. The Kremlin cathedrals and churches,

with their multiple domes, look like huge chandeliers. The onion shape results

from the idea of prayer as a soul burning towards heaven, which connects the

earthly world with the treasures of the afterlife. Every attempt to explain the

onion shape of our church domes by utilitarian considerations (for instance,

the need to preclude snow from piling on the roof) fails to account for the

most essential point, that of aesthetic significance of onion domes for our

religion. Indeed, there are numerous other ways to achieve the same utilitarian

result, e.g., spires, steeples, cones. Why, of all these shapes, ancient

Russian architecture settled upon the onion dome? Because the aesthetic

impression produced by the onion dome matched a certain religious attitude. The

meaning of this religious and aesthetic feeling is finely expressed by a folk

saying – "glowing with fervour" – when they speak about church

domes"43.

The idea of "fire" concerning the symbolism

of the onion domes after E.N.Trubetskoy was conducted by M.P.Kudryavtsev and

G.Ya.Mokeev44. I.A.Bondarenko joined this position45.

But it should be noted that any search for symbolism

of any element of Orthodox churches in isolation from the study of the genesis

of these forms will inevitably lead to a purely subjective views on the level

of “I see so”, easily disproved by statistics, facts, and by extension of other

equally subjective opinions that appear no less convincing.

For example, in Ancient Russia a relatively small

number of domes was covered with gold (only of the largest churches that had

the richest churchwardens), and numerous green, blue, brown and black domes

cause no association with fire.

On a subjective level it would be fairer to compare

the onion domes not with fire, but with an arrowdome, a drop of water or of a

head of a warrior wearing a helmet. The latter interpretation – a head of a

warrior – in Ancient Russia, apparently, was the most frequently used: it is

confirmed by the fact that the domes were called “heads” or

"foreheads", the drums – “necks”, and the roofs of churches –

"shoulders".

Accordingly, since any attempt to interpret symbolic

of the domes were and are extremely subjective, we can conclude only that in

XIII century in Russia keeled archivolts of arched gables, portals and windows

appeared, and in Gothic Western Europe and Arab East – a large number of

erected arches. This fully explains genesis of the onion domes in terms of

theory and history of architecture: craftsmen, who accommodated wooden

structures over the cupolas of temples, were only to combine and apply these

already known forms in their work.

This does not in any way belittle the significance of

this invention of ancient craftsmen, which had an aesthetic self-sufficiency

and gave the churches a fundamentally new shape without significant material

costs, and this was particularly important in difficult economic circumstances

of Mongol yoke.

V

Genesis

of the helmet domes

In Chapter 2 we have seen that existence of helmet

domes in XIV-XVI centuries is not proved. If the domes of "non-onion"

form were erected, then extremely rarely, and they were as soon as possible

replaced by the commonly used form – onion. At the turn of XVI and XVII

centuries all the domes, without exception, had onion shape.

By idea, later the domes were to keep onion shape, or

take the characteristic form of Baroque. Nevertheless, we see the helmet domes

on many images of XVIII-early XIX century, which are not plans or panoramas,

but still worthy of credibility (see Section 8 of the statistical illustrative

material).

Of course, the number of the helmet domes on the

images of XVIII-early XIX century is negligible, comparing with the huge number

of the onion domes on the plans and panoramas (see Sections 6 and 7 of the

statistical illustrative material). Apparently, such a correlation occurred

also in reality. But we should present some observations that can help us at

least approximately describe genesis of the helmet domes.

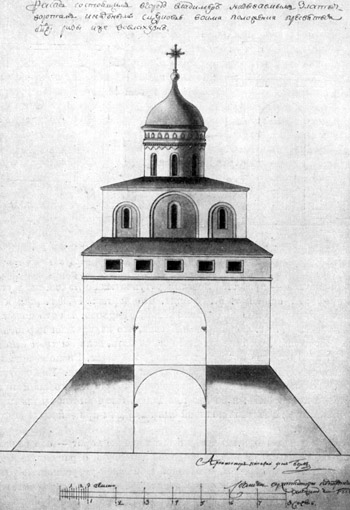

First, the helmet dome is featured on the drawing of

Golden Gate of Vladimir by Von Berk and Gusev (1779, fig. C-32) and the image

of St. Demetrius Cathedral on one of panoramas of Vladimir in 1801 (Fig. C-33),

and that gave the appearance of "surviving of the ancient domes to our

days" and predetermined the stereotypical view of such domes as

"widespread in pre-Mongol North-Eastern Russia".

In Chapter 2 we have shown the inconsistency of this

stereotype. Let us add that we see the onion domes on Golden Gate and St.

Demetrius Cathedral on the "drawing" of Vladimir of 1715 (Fig. C-27),

and on one of the images of Vladimir of 1801 (Fig. C-34). But the last image is

quite conditional, and there is no doubt that in reality St. Demetrius

Cathedral in 1801 had the helmet dome, shown on a much more detailed and

professional view of Vladimir of that year (Fig. C-33, C-35).

So, the helmet dome was arranged on St. Demetrius

Cathedral between 1715 and 1801. May be, even not later than 1779, since it is

likely that Berk and Gusev were guided by it in developing of their version of

the reconstruction of Golden Gate (Fig. C-32). They could not orient at

Assumption Cathedral: in all pictures of Vladimir of 1801 it is depicted with

the onion domes (Fig. C-33), about which we know that they existed in reality

and were replaced by the helmet domes during the restoration of 1888-189145.

Secondly, there was a period (probably brief) in XVIII

century, when Assumption Cathedral had helmet domes: that is shown by helmet

structures on cupolas with traces of plaster, nails and metal46. It

is important to note that those structures were made of brick, so they could

not be made in pre-Mongol times – only to XVIII century (the

"drawing" of 1715 shows the onion domes on the cathedral – see Fig.

C-27).

Third, Archangel Cathedral of Moscow Kremlin has a

double central cupola (Fig. 1147). On the upper one there is a large

under-cross stone. If the temple had always had only an onion dome (shown on

the plans of Moscow of the turn of XVI-XVII centuries), the construction of the

upper cupola would not have made any sense: a carcass of any configuration can

be built on a cupola.

Fig. 11. Archangel Cathedral of Moscow

Kremlin. Section.

Consequently, at some moment (not

before 1707, when the cathedral with the onion domes is depicted on the

engraving by P.Pikart – see Fig. C-28) the central onion dome was replaced by

the helmet, which we see on the image by M.F.Kazakov of 1772 (see Fig. C-36).

Then the onion dome, first shown on the image by F.Kamporezi of 1780s (see Fig.

C-37), was re-arranged.

Fourth, we can see the helmet dome on the Assumption

Bell-tower of Moscow Kremlin in 1800 (see Fig. C-38). The plans of XVII century and the engraving by P.Pikart of 1707 show

that its dome had onion shape (see Sections 6 and 7 of the statistical

illustrative material).

Fifth, we see the helmet dome on

Church of Nativity of the Virgin in Gorodnya on the drawing by A.Meyerberg of

1661 (see Fig. C-29).

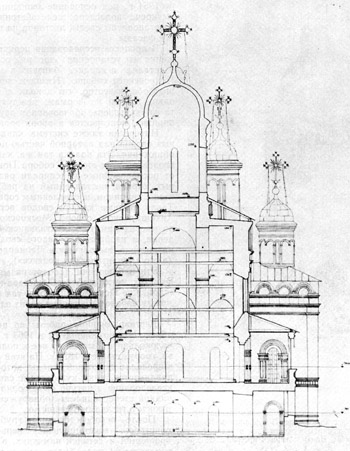

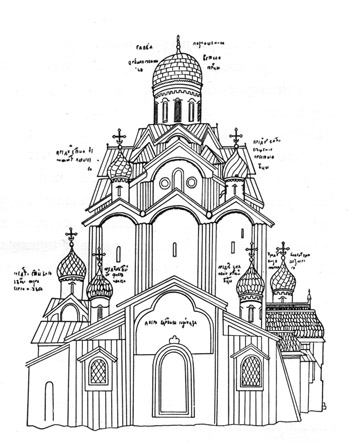

Sixth,

under the existing onion domes of Trinity Church in the village Chashnikovo

(see Fig. 2) the brick helmet dome with traces of nails has preserved. The

research of the remainings of tile on this dome48 showed that likely in the second half of XVII

century the domes of

Let us note that we must consider the reconstruction of the original form of the

dome of

Seventh, a large conical under-cross stone was found

on the central cupola of the

Fig. 12. Church of Transfiguration in

Bolshye Vyazemy. Section.

Eighth, we see the helmet dome on the image of Trinity

Cathedral of Troitse-Sergiev Lavra of 1745 (Fig. C-31), despite the fact that

the onion dome is depicted on the nearby Nikon Church.

Ninth, we see the central helmet dome, combined with

small onion domes, on Trinity Cathedral in Pskov in the late XVII century (see

Fig. C-30).

We can conclude of all the above observations the

following: the helmet domes appeared in XVII-XVIII centuries in fairly large

quantities as a stylization of "antique" (i.e., as something between

the onion domes and the simplest cupola coatings).

Then, as a rule, these domes were again replaced by

the onion ones (probably because of evolution of aesthetic preferences of

clergy and churchwardens).

The exception was Demetrius Cathedral in Vladimir, the

onion dome of which was converted to the helmet form in the end of XVIII

century, was preserved in XIX century and, apparently, determined the

stereotype of "antiquity" of this form of domes and their

"common use in pre-Mongol North-Eastern Russia". Later this

stereotype, the incorrectness of which we have shown in Chapter 2, extended to

Ancient Russian architecture of XIV-XVI centuries.

Conclusion

Let us summarize our study of the forms of the domes

of Ancient Russian temples.

1. In pre-Mongolian time:

– everywhere (including North-Eastern Russia) the

simplest cupola coatings were distributed, usually with under-cross stones;

– existence of the onion domes is conventionally

proved, but their wide dissemination is not proved;

– existence of helmet domes is not proved, any

allegations of their existence as a "transitional form from a cupola to an

onion" are conjectures;

– existence of any other form of domes (umbrella,

conical, etc.) is not proved.

2. Since the second half of XIII century until the end

of XVI century:

– the onion domes occurred everywhere, including

hipped architecture of XVI century;

– existence of the helmet domes is not proved;

– the simplest cupola coatings of pre-Mongolian time

theoretically could be preserved on some minor temples throughout the whole

period under review, but by the end of XVI century they were universally

replaced by the onion domes;

– existence of any other form of domes (umbrella,

conical, etc.) is not proved.

3. Since the end of XVI century until the middle of

XVII century:

– the onion domes occurred everywhere, including

hipped architecture;

– existence of any other form of domes is not proved.

4. Since the middle of XVII century until the end of

XVIII century many onion domes were replaced by helmet ones as a stylization of

"antique". In most cases, in a few decades the onion domes were newly

built on the temples.

APPENDIX

Statistical illustrative material

Statistics by the old

images was calculated by their total number, irrespective of the number of

temples or domes on a particular image.

Images of houses, towers,

kivories or stylized passages were not included in the analysis.

Randomness (and, hence,

objectivity) of the statistical illustrative material is provided as follows:

the analysis included all the images of temples on ancient icons, miniatures,

works of applied art, plans etc. of all the books on history of art and

architecture, located in the personal library of the author (since

pre-Mongolian time until the end of XVII century – 147 images; since the end of

XVI century only plans, panoramas and drawings were included into the

analysis). In addition, the statistical illustrative material included 13

images of XVII-XVIII centuries.

Hereby we show only some

illustrations, which are the most important for our study.

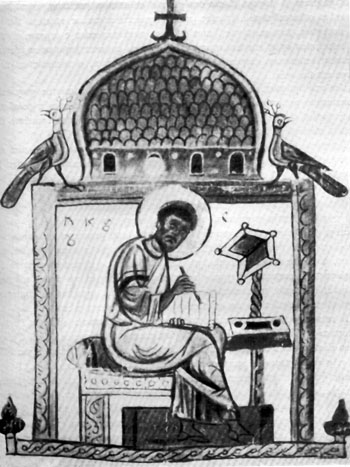

Section 1. Pre-Mongol

time.

In total,

this section deals with 9 images, among them:

6 – simple cupola

coatings;

1 – umbrella dome;

2 – onion domes.

Fig. C-1. Great Zion of Sophia of Novgorod.

XI-XII centuries.

Fig. C-2. Detail of

Suzdal Golden Gate. The beginning of XIII century.

Fig. C-3. St.Luke.

Miniature from Dobrilovo Gospel (Galician-Volyn school). 1164.

Section 2. The second half of XIII

century.

In total, this section deals with 3

images, on all three we see onion domes.

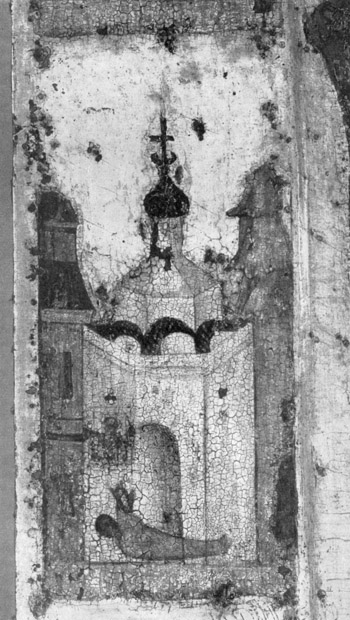

Fig. C-4. “The image of

Church”. Thumbnail of Hamartolas manuscript from Tver. About 1294.

Fig. C-5. “The Burial of

David”. Thumbnail of Tver Hamartolas manuscript.

Fig. C-6. Prince

Jaroslav Vsevolodovich with a temple. Fresco from the Church of Our Saviour on

Nereditsa. About 1246.

Section 3. XIV century.

In total, this section deals with

17 images, including:

11 – certainly with onion domes;

2 – with probable onion domes;

1 – with a combination of onion

domes and a simple cupola coating;

3 – with simple cupola coating,

umbrella and conical domes.

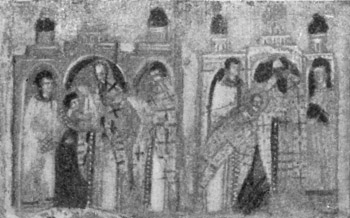

Fig. C-7. Introduction to the temple. An icon from Krivoy village. Novgorod school. The first half of XIV century.

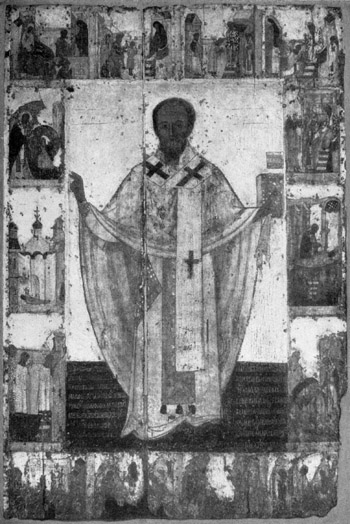

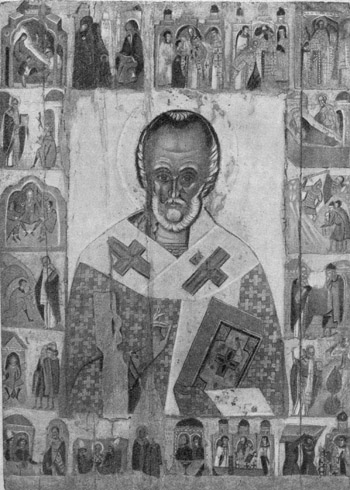

Fig. C-8. Nicola

Zaraisky and his life. Kiev School. Beginning of XIV century.

Fig. C-9. Nicola

Zaraisky and his life. Fragment.

Fig. C-10. St. Nicolas

and scenes from his life. Kolomna. The middle of XIV century.

Fig. C-11. St. Nicolas

and scenes from his life. Fragment.

Fig. C-12. St. Nicolas

and scenes from his life. Fragment.

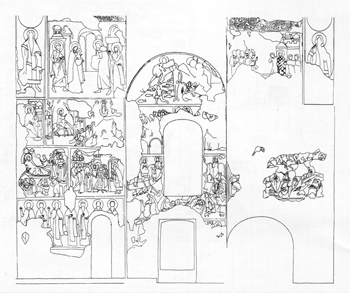

Fig. C-13. Frescoes of

the southern wall of the cathedral of Snetogorsky monastery. 1313.

Section 4. XV century.

In total, this

section deals with 23 images, including:

17 – with certain

onion domes;

1 – with probable onion dome;

2 – with

combinations of helmet and onion domes;

1 – with a helmet

dome;

1 – with a simple

cupola coating;

1 – with a conical

dome.

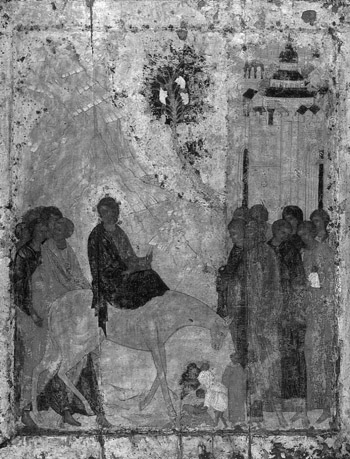

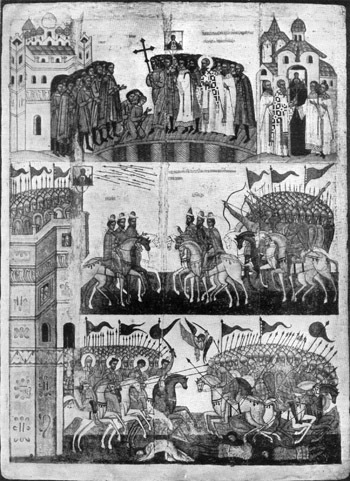

Fig. C-14. Entry into

Jerusalem. Icon from Annunciation Cathedral in

Moscow Kremlin. 1405.

Fig. C-15. Metropolitan

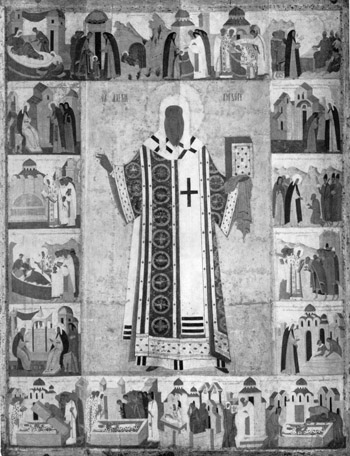

Oleksiy and his life. Moscow School. End of XV-beginning of XVI century.

Fig. C-16. Metropolitan

Oleksiy and his life. Fragment.

Fig. C-17. Happy about

you. Pskov school. End of XV century.

Fig. C-18. Igor with

Gentiles goes to the idol of Perun, and Christians – to the Church of St.

Elijah. Thumbnail of Radzivil Chronicle.

Fig. C-19. Battle of

people of Novgorod against the people of Suzdal (Miracle of the Icon of the

Sign). Novgorod school. The second half of XV century.

Fig. C-20. Canon of

Cyril Belozersky monastery. Frontispiece. 1407.

Fig. C-21. Nicola

Mozhajskij. Moscow School. The middle of XV century.

Fig. C-22. Great Zion of

Vladimir Assumption Cathedral. The top, made by Moscow masters, is dated by

1486.

Section 5. XVI century.

In total, this section deals with

66 images, including:

57 – with certain

onion domes;

2 – with probable onion domes;

1 – with the

combination of helmet and onion domes;

1 – with the

combination of simple cupola coverage and onion dome;

2 – with

combinations of conical and onion domes;

1 – with an

umbrella and conic domes;

2 – with simple

cupola coatings;

1 – with

"gothic" urban landscape.

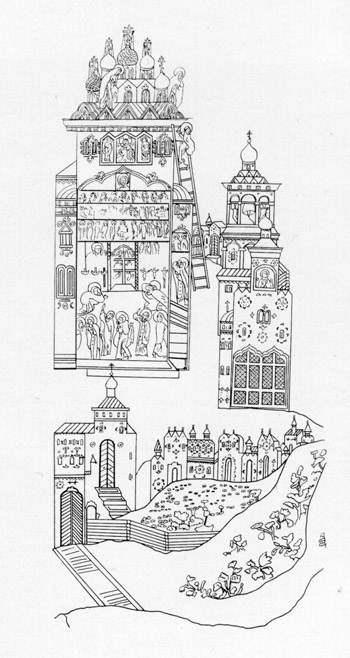

Fig. C-23. Consecration of the Intercession

Cathedral on the Moat. Thumbnail of Litsevoy

Chronicle of XVI century.

Fig. C-24. Assumption Cathedral in Vladimir. Thumbnail of Litsevoy Chronicle.

Fig. C-25. Gregory Church, "Great Armenia" and Varlaam

in Varlaam-Khutyn Monastery in Novgorod. Drawing from the icon “Vision of

Sacristan Taras”. 1536.

Section 6. Plans of Moscow of the

end of XVI-early XVII centuries.

In total, this section deals with 7

images, all 7 – with onion domes.

Fig. C-26.

“Kremlenagrad”. Early 1600s. Fragment.

Section 7. Plans and panoramas of

Russian cities of XVII-early XVIII century.

In total, this section deals with

24 images, all 24 – with onion domes.

Fig. C-27. Vladimir.

"Drawing" of 1715.

Fig. C-28. Panorama of

Moscow by P.A.Pikart. About 1707. Fragment.

Section 8. Images of XVII-beginning

of XIX century.

Fig. C-29. Church of

Nativity of the Virgin in Gorodnya. Drawing by A.Meyerberg. 1661.

Fig. C-30. Pskov, Holy

Trinity Church of 1365-1367. Image of the end of XVII century.

Fig. C-31. Trinity

Cathedral with Nikon Church. Drawing of 1745.

Fig. C-32. Golden Gate

in Vladimir. Drawing by Berk and Gusev. 1779.

Fig. C-33. Demetrius

cathedral in Vladimir (with the helmet dome). 1801.

Fig. C-34. Demetrius

Cathedral in Vladimir (with the onion dome). 1801.

Fig.

C-35. Assumption and Demetrius cathedrals. A fragment of the image of

Vladimir. 1801.

Fig. C-36. The beginning

of construction of Kremlin palace by the draft

of V.I.Bazhenov. 1772. Drawing by M.F.Kazakov.

Fig. C-37. Moscow Kremlin. Drawing by F.Kamporezi. 1780s.

Fig. C-38. Ivanovskaya Square of Kremlin. Watercolor

of the workshop of F.Y.Alexeev. 1800-1802.

NOTES

1. A.S.Partina. Architectural terms. Illustrated

Dictionary. M., 2001.

2. N.N.Voronin.

Architecture of North-Eastern Russia of XII-XV centuries. M., 1961-1962

(hereinafter – Voronin, 1961-1962). Vol. 1, p. 154.

3. Architectural

Monuments of Moscow region. Vol. 2, p. 257.

4. Theory and practice

of restoration work. ¹ 3. M., 1972. P. 94.

5. Such position was

expressed mostly consistently in the early twentieth century in the work of

A.P.Novitsky (A.P.Novitsky. Onion shape of the domes of Russian churches.

Proc.: Moscow Archaeological Society. Antiquities. Proceedings of the

Commission for conservation of ancient monuments. Vol. III . M., 1909. P.

349-362).

6. D.V.Aynalov. On some

episodes of miniatures of Radzivil Chronicle. Proc.: "Proceedings of the

Department of Russian Language and Literature of the Academy of Sciences, ¹ 13,

vol. 2. St.Petersburg, 1908. P. 309; A.V.Artsikhovsky. Miniatures of

Koenigsberg (Radzivil) Chronicle. Leningrad, 1932; B.A.Rybakov. The windows in

the extinct world (about the book of A.V.Artsikhovsky "Old miniatures as a

historical source"). Proc.: Reports of MSU. Vol. IV. M., 1946. P. 50;

B.A.Rybakov. "Lay" and its contemporaries. M., 1971. P. 12.

7. N.N.Voronin. An

architectural monument as a historical source (note to the question). Proc.:

Soviet Archaeology. Vol. XIX. M., 1954. P. 73.

8. In particular,

A.P.Novitsky thought so (A.P.Novitsky. Ordinance. Cit., P. 357).

9. A.M.Lidov. Jerusalem

Edicule. On the origin of the onion domes. Proc.: Iconography of architecture.

M., 1990. P. 57-68.

10. A.M.Lidov.

Ordinance. cit., p. 58.

11. I.A.Bondarenko. On

the origin of onion shape of the church domes. Proc.: Style of architecture.

Petrozavodsk, 1998. P. 105-113.

12. Ibid. 109.

13. V.N.Lazarev.

Byzantine and Russian art. M., 1978. P. 246.

14. We shall

collectively call artists the painters, fresco, miniatures and other masters of

ancient art.

15. A.M.Lidov.

Ordinance. cit., p. 59.

16. Website

http://forum.openarmenia.com.

17. Die Grabeskirche zu

Jerusalem. Geschichte – Gestalt – Bedeutung. Regensburg, 2000. P. 151.

18. Ibid. P. 150.

19. Some people consider

that the "dome" of Edicule is an apparatus for the generation of

"Holy Fire". In this case, the author refrains from comments.

20. I.A.Bondarenko.

Ordinance. cit.

21. Ibid. P. 109.

22. N.N.Voronin.

Ordinance. cit., vol. 2, p. 105.

23. Ibid. 156.

24. For details, see:

S.V.Zagraevsky. The architectural history of Trifon church in Naprudnoe and

origin of cross-like vault. M., 2008.

25. In connection with

the foresaid, it should be noted that A.M.Lidov, citing the opinion of some

researchers, in particular, the reconstruction by N.N.Sobolev (N.N.Sobolev. The

project of reconstruction of the monument of architecture – St. Basil Cathedral

in Moscow. Proc.: Architecture of the USSR, ¹ 2, 1977. P. 48), believed that

the onion domes of the cathedral of the Intercession on the Moat appeared in

the time of Fedor Ioannovich. We can not agree with this position: the

miniature of Litsevoy Chronicle of the middle of XVI century (see Fig. C-23) is

absolutely clear image of the consecration of the Cathedral of Intercession

with onion domes.

26. S.M.Soloviev.

History of Russia since ancient times. Publication is on the website

http://holychurch.narod.ru.

27. Voronin, 1961-1962.

Vol. 1, p. 474.

28. Russian chronicles.

Vol. 9: Typographical Chronicle. Ryazan, 2001. P. 270.

29. Voronin, 1961-1962.

Vol. 1, p. 356.

30. Ibid. P. 398.

31. Russian chronicles.

Vol. 4: Lviv Chronicle. Ryazan, 1999. P. 73.

32. Russian chronicles.

Vol. 10: First Novgorod Chronicle. Ryazan, 2001. P. 386.

33. A.F.Bychkov. Summary

chronicler of Holy Trinity St. Sergius Lavra. Proc.: A. Gorsky. The historical

description of Holy Trinity St. Sergius Lavra. M., 1890. Appendix. P. 177.

34. A.P.Novitsky.

Ordinance. cit.

35. In particular, J.

Fergusson believed so (J. Fergusson. History of Architecture. Vol. 2. London,

1867. P. 50).

36. I.A.Bondarenko.

Ordinance. cit., p. 106.

37. B.V.Veimarn,

T.P.Kapterev, A.G.Podolsky. Art of Arabia, Syria, Palestine and Iraq. Proc.:

Universal History of Art. V. 2, Bk. 2. M., 1961.

38. G.K.Vagner. Style

formation in architecture of Ancient Rus (return to the problem). Proc.:

Architectural heritage. Vol. 38. M., 1995. P. 25.

39. O.O.Shchelokov.

Construction of carcasses of the domes of churches in Vladimir Province.

Publication is at the website http://rusarch.ru.

40. S.D.Sulimenko.

Architecture and dialogue of cultures (for example, forms of symbolization

endings Russian Orthodox church). The article is on the website

www.raai.sfedu.ru.

41. N.L.Pavlov. Altar.

Stupa. Temple. Archaic universe in Indo-European architecture. M., 2001. P. 13.

42. In particular, see:

S.V.Zagraevsky. Yuri Dolgoruky and Old Russian white-stone architecture. M.,

2002. P. 124.

43. E.N.Trubetskoy.

Three Essays on Russian icon. 1917. Novosibirsk, 1991. P. 10.

44. M.P.Kudryavtsev,

G.Ya.Mokeev. On a typical Russian church of XVII century. Proc.: Architectural

heritage. ¹ 29, 1981. P. 72.

45. Voronin, 1961-1962.

Vol. 1, p. 360.

46. T.P.Timofeeva. The

restoration of Assumption Cathedral in 1888-1891. Proc.: State Vladimir-Suzdal

Historical and Architectural Museum-Reserve. Research materials. ¹ 11.

Scientific-practical conference (November 17, 2004). P. 99.

47. D.A.Petrov. The

internal space of two churches of the beginning of XVI century and Archangel

Cathedral of Moscow Kremlin. Proc.: Archives of architecture. Vol. 9. M. 1997.

P. 101.

48. Architectural

heritage. Vol. 18. M., 1969. P. 19-23.

49. Theory and practice

of restoration work. ¹ 3. M., 1972. C. 94.

50. Ibid.

© Sergey Zagraevsky

To the page “Scientific works”