To the page “Scientific works”

S. V. Zagraevsky

New researches of Vladimir-Suzdal museum’s

architectural monuments

Published in Russian: Çàãðàåâñêèé Ñ.Â. Íîâûå èññëåäîâàíèÿ ïàìÿòíèêîâ àðõèòåêòóðû Âëàäèìèðî-Ñóçäàëüñêîãî ìóçåÿ-çàïîâåäíèêà. M.: Àëåâ-Â, 2008. ISBN 5-94025-099-8

Chapter

1.Organization of production and processing of white stone in ancient Russia

Chapter 2. The

beginning of “Russian Romanesque”: Jury Dolgoruky or Andrey Bogolyubsky?

in Suzdal in

1148 and the original view of Suzdal temple of 1222–1225

Chapter 4.

Questions of date and status of Boris and Gleb Church in Kideksha

Chapter 5.

Questions of architectural history and reconstruction of Andrey Bogolyubsky’s

Assumption

Cathedral in Vladimir

Chapter 6.

Redetermination of the reconstruction of Golden Gate in Vladimir

Chapter 7.

Architectural ensemble in Bogolyubovo: questions of history and reconstruction

Chapter 9.

Questions of the rebuilding of Assumption Cathedral in Vladimir by Vsevolod the

Big Nest

Chapter 10.

Questions of the original view and date of Dmitrievsky Cathedral in Vladimir

Chapter

7.

Architectural

ensemble in Bogolyubovo:

questions

of history and reconstruction

1. White stone citadel with on-gate church

N.N. Voronin wrote: “The

construction of Bogolyubovo castle of Prince Andrey – one of the most

interesting pages of history of culture of Ancient Russia in general and in

particular of Vladimir”1. Indeed, we do not know another such a

large complex of white stone buildings in pre-Mongolian

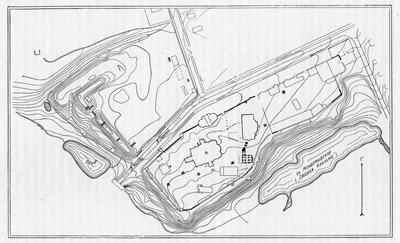

The contemporary town of Bogolyubovo (Vladimir region)

is located approximately

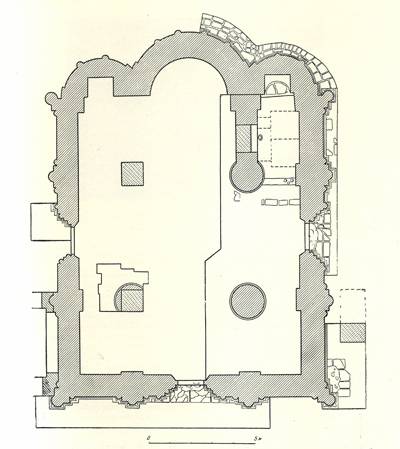

The outlines of the western part of the city are well

traced on the ground, and also at the plan by N.N. Voronin3

(Fig. 56). The south-western corner of the fortifications was formed by the

cape, the north-western – by the curve of ramparts. The remains of a rampart

are preserved from the north-west. The city center was located where there was

the Prince's palace – near the

Fig.

56. Plan of the ancient part of the modern town of

Archaeological researches of 1954, held under the

direction of N.N. Voronin, showed the loyalty of the messages of

chroniclers and scholars of XIX century that the city of

V.K. Emelin, the modern researcher of the

monument, believed that only the princely court near the church of Nativity of

the Virgin had white stone walls (see Section 2), and the next line of defense,

according to V.K. Emelin, was a wooden citadel, which had white stone gate

with white stone church of St. Andrey on it (the walls of the citadel began at

the western city walls, approximately followed the line the modern walls of the

monastery to the bell-tower, and then turned to the south-east and reached the

precipice to the Klyazma), and the city extended to the north from the citadel

and was fortified by ramparts with wooden walls5.

But we can not agree with V.K. Emelin that only

the Prince’s courtyard had white stone walls: in Section 2 we shall see that

its area was very small, and in fact it was a fortified complex of buildings,

i.e. the Chronicles could hardly tell about it as about a "city of

stone"6. And taking into consideration that the studies by

N.N. Voronin discovered the remains of white stone walls in the southern

corner of the city and on the west line of ramparts (these excavations are

shown at Fig. 56)7, we must assume that the walls were made of white

stone around the whole perimeter, as N.N. Voronin considered8.

The length of these walls is estimated at about 1-

Let us note

that if there was a citadel in the city (by V.K. Emelin), then it is likely

that the walls also were built of white stone. But this position has not been

confirmed by archaeological data.

E.E. Golubinsky9 and N.N. Voronin10

believed that the main purpose of the city of

However, the city of

We can evaluate only approximately the size of these

suburbs. The location of Dobroye village and of an ancient dwelling site near

Sungirevsky ravine (which became a small town in XII century12)

between Bogolyubovo and Vladimir, as well as the elongation of the

fortifications of Vladimir to the east13 (see Fig. 45), lets us

suggest that the eastern part of Vladimir and the western part of Bogolyubovo

during the reign of Andrey constantly "stretched" to each other, and

in early 1170s the suburbs might have actually formed a coherent whole

(including Dobroye village and the town near Sungirevsky ravine).

Thus, Bogolyubovo was a "full-fledged" city

in 1160-1170s, quite comparable by size and significance to Suzdal,

Yuryev-Polsky or Dmitrov. And since there was the residence of the Grand Prince

in Bogolyubovo, we must make one more principal conclusion: in the time of

Andrey not Vladimir, but Bogolyubovo was the capital of

So it is no coincidence, that after the death of

Andrey and the foundation of the monastery in the former princely castle14

the city fell into neglect only several centuries later, when the economic and

strategic situation in

According to

archaeological researches, the walls were built in half-rubble

technology of large white stone blocks on lime mortar

mixed with wooden coal18. Blocks were treated somewhat more roughly

than wall blocks of pre-Mongolian temples of North-Eastern

N.N. Voronin assumed on the basis of

stratigraphic analysis of remains of the southern tower that the construction

of white stone fortifications took three building seasons19. Basing

on the message of Fourth Novgorod Chronicle under 1158 "and founded the

city of

But we, basing on the fact that, as we have shown

above, the city had big suburbs, can assume that Bogolyubovo was developing by

the most typical way for fast-growing Russian cities:

– in the late 1150s the princely palace (see Section

2), the Church of Nativity of the Virgin (see Section 3) and the first small

wooden fortress (which later perhaps became the citadel) were constructed;

– at the next stage of development, the city walls

were substantially expanding in the direction of the "field";

– at the next stage (possibly already in the late

1160s and early 1170s), the wooden walls were replaced by white stone.

This position is confirmed by the fact that the

message of “Brief Vladimir Chronicler”, which describes the arrival of Andrey

to Suzdal from Kiev and the construction of Bogolyubovo, says nothing about

stone walls: “And then Andrey Yurievich came from Kiev, and built the city of

Bogolyubovo, and surrounded it with ramparts, and erected two stone churches,

and stone gates, and the palace”22. The "city of stone" is

mentioned only in the chronicle messages, which give general characterization

of Bogolyubsky’s reign23.

Accordingly, we can tentatively date the white stone

fortifications of Bogolyubovo by the border of 1160s and 1170s.

Probably one of two stone churches, mentioned in

“Brief Vladimir Chronicle” – the Church of Nativity of the Virgin (see Section

3), second – the Church of Intercession on the Nerl (as it is evidenced by the

message of First Novgorod Chronicle: "And he erected for her (Mother of

God – S.Z.) the temple on the Klyazma river, two stone churches in the name of

Holy Mother of God"24). “Brief Chronicle” says nothing about

the on-gate temple, but we can provide some indirect evidence that it existed

and was devoted to Andrey the First Called:

– in ancient

– “Life of Andrey Bogolyubsky” (the beginning of XVIII

century) states: "built the stone gate and the church on it and gave it

the namesake of St. Apostle Andrew the First Called"25;

– the on-gate church, which was erected in the

monastery in late XVII century, was also dedicated to Andrew the First Called

(and the traditions of consecration were usually respected in ancient

monasteries).

However, we do not know where the gate of XII century

was – at the place of the existing bell-tower or somewhere else. The answer to

this question can be got only by new archaeological researches.

2. Prince's palace-"burg"

The message of “Brief Vladimir Chronicle” does not say

explicitly that the palace was made of stone (the latter could relate only to

the gate – “and the stone gate and the palace”). But the archaeological investigations

of 195026 indicate that the palace was built of white stone (at

least in part).

Let us try to

clarify the purpose of two buildings, which remained from the palace – the

stair-tower and the passage27 between it and the

Fig.

57.

V.K. Emelin drew attention to the fact that the

tower faces to the west by the narrow windows-loopholes, and to the east – by

the "civil" three-part window, and expressed the doubt that between

the stair-tower and the choir of the Church of Nativity there was a large stone

passage, built without a specific need (it would have been easier to attach the

tower to the wall of the temple). In this regard, the researcher suggested that

under the arch a gate was located, which led into a fortified princely

courtyard28.

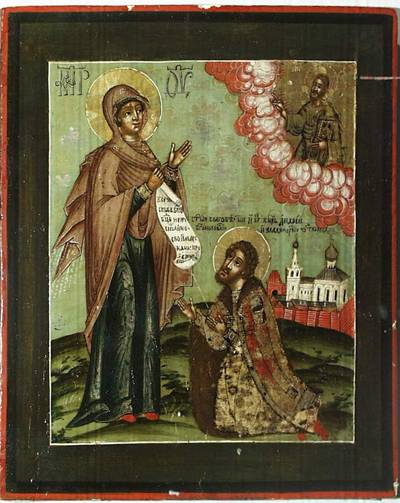

We shall add that the narrow windows and loopholes are

seen in quite a realistic picture of the passage at the XVII century icon of

Our Lady of Bogolyubovo29 (Fig. 58). The fact that the contemporary

rough, asymmetrically arranged rectangular windows of the passage are not

primary, is confirmed by the observation of clearly visible traces of numerous

turnings of the passage walls under the arcature-columnar zone between the

capitals and bases of columns (Fig. 59). Perhaps the primary windows of

“loophole” form were in each interval between five columns, i.e. there were

four windows in the passage, as it is depicted at the icon. However, we can not

exclude the option that there were two primary windows in the passage, but the

icon painter showed four by the number of the spaces between the columns.

Fig.

58. Icon of Our Lady of Bogolyubovo. XVII century.

Fig. 59.

Western wall of the passage. Arrows

indicate the traces of turnings.

In this regard, we fully support the

hypothesis of V.K. Emelin that the western facades of the stair-tower and

the temple were included into the complex of fortifications of the Prince's

courtyard, and the gate, which led to this court, was located in the arch under

the passage. That was confirmed by studies, conducted by the author of this

book in cooperation with T.P. Timofeeva in 2006: symmetrical traces of

turnings were found at the places under the arch, where the gate hinges could

be situated (Fig. 60).

Fig.

60. Arch under the northern passage. The traces of turnings at the places of

the gate hinges are marked by arrows.

It may seem that the imposts under the arch could

interfere the gate to open. However, according to the observation of

T.P. Timofeeva, the exterior blocks of imposts were replaced later, and,

most likely, there were top gate hinges in their place. Accordingly, if the

gates were opened to the outside, the imposts did not interfere.

And since, as we have shown above, the passage had

narrow windows-loopholes, we must assume that it also played the role of the

on-gate battle site. Perhaps, there was one more – open – battle site on the

vault of the passage.

The sequence of erection of the preserved complex of

northern extensions to the

– firstly the church was built;

– then the lower tier of the stair-tower;

– then (after a sufficiently long time – perhaps

several years) the arch with the passage;

– then (after a sufficiently long time – perhaps

several years) the upper tier of the tower.

We can bring some proofs for this situation.

First, the arch with the passage is

"attached" to the northern wall of the

Fig.

61. The place of junction of the northern passage to the wall of the

N.N. Voronin, paralleling in his studies the

galleries of the

This stereotype is very stable. For example, P.A.

Rappoport wrote: “It is obvious that the builders of ancient

In other words, N.N. Voronin and

P.A. Rappoport believed that ancient Russian craftsmen were doing some kind

of "Sisyphean labor", having no other reason than "an original

logic". As the main example of such a “Sisyphean labor”, those researchers

cited the arcature-columnar zone of the northern wall of the

However, we see no “original logic’, and moreover

“Sisyphean labor” in the work of Bogolyubovo craftsmen. Their actions are seen

absolutely logical from contemporary positions, and we can justify that.

There is no doubt that initially the

It is much more

likely, that at the time of construction of the

Accordingly, the actions of the craftsmen, who

completed the arcature-columnar zone of

We have finished the consideration of the first proof of the sequence of erection of the preserved complex of

northern extensions to the

The second proof: the arch with the passage is

"attached" to the stair-tower as well as to the northern wall of the

church – without masonry bond and united rubble.

Third: the lining of the masonry of the arch with the

passage coincides neither with the lining of the masonry of the church, nor

with the lining of the masonry of the tower.

Fourth: the lower tier of the stair-tower, including

its adjacent to the arch with the passage southern wall, is solid and once

erected structure. That is proved by the clear lining of masonry and

conjugation of the square plan of the external walls with intricate internal

volume (circular in plan and having a spiral system of vaults over the spiral

staircase) by the stone blocks of complicated form35.

Fifth: the construction of the upper tier of the

stair-tower (i.e. of the closed site, where the staircase leads) later than the

arch with the passage was "attached" to the lower tier, is proved by

the existence of the doorway to the passage and of the arcature-columnar zone,

similar to the zone on the external walls of the transition, in the interior of

the upper tier.

Accordingly, while there was no upper tier of the

tower, the northern passage ended by the wall, which was decorated by

arcature-columnar zone and had a doorway. After the building of the upper tier

of the tower, the northern wall of the passage with the doorway and

arcature-columnar zone turned out to be in the interior of this tier (Fig. 62).

Fig.

62. The interior of the upper tier of the stair-tower.

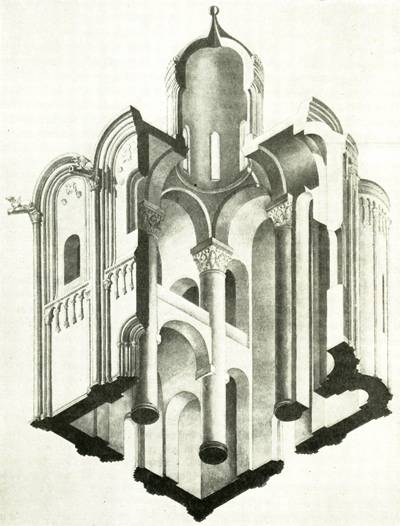

Let us consider the question, how the palace-temple

complex could look in general.

N.N. Voronin believed on the basis of excavations

near the southern wall of the church that it had a similar construction – a

stair-tower with a passage over an arch (the reconstruction the whole complex

of buildings around Nativity Church by N.N. Voronin is presented at Fig.

63)36.

Fig.

63. The complex of buildings around the

But it is shown on Fig. 56 that there was very little

space the south and east of the Church of Nativity of the Virgin for the palace

buildings (even taking into account the fact that in the pre-Mongolian time the

precipice to Klyazma was slightly farther away from the temple). It is unlikely

that the courtyard was greatly elongated to the north-east – then its form

would have been too narrow and curved.

Therefore, if we assume that the Prince's courtyard

had "full-fledged" walls at the south, north and east, then the free

space inside it would have been too small (by V.K. Emelin, it could be

only a few hundred sq. m37). This area needed also some vacant

space, where the preserved arch led. It turns out that if the Prince's palace

had been a detached building within a fortress (with a gap at least 2-

This problematic situation is solved as follows: the

walls of the palace also were the walls of the princely courtyard to a

considerable extent, i.e. the yard was not just a fenced area, but a fortified

complex of buildings. The system of fortifications could contain most of the

palace buildings (they might have looked like N.N. Voronin depicted them

on his reconstruction, but without many arches in the walls). In the time of

Bogolyubsky many German and North Italian "burgs" were built on the

similar principles, and many centuries later so

Accordingly, the remains of white stone masonry,

opened by the excavations to the south of the

Was that

southern complex of buildings symmetrical to the northern? We believe that it

was not fully symmetrical, but similar. This is proved by the fact that the

western part of the southern wall of the existing

Fig.

64. Existing

This position is confirmed by the archaeological

research of N.N. Voronin, who showed that the southern extensions were

similar to the northern37 and still existed in XVII century38.

The fact that the southern extension were not reflected at the XVII century

icon of Our Lady of Bogolyubovo (see Fig. 58) is not surprising: the temple is

depicted on the edge of the icon, and these additions could not fit the

picture.

Judging by the upper level of decoration of the lower

tier of the western part of the southern wall of the existing Nativity church,

the unpreserved southern passage joined the church wall somewhat higher than

the northern, and this is consistent with our understanding of the different

time of the construction of various parts of the

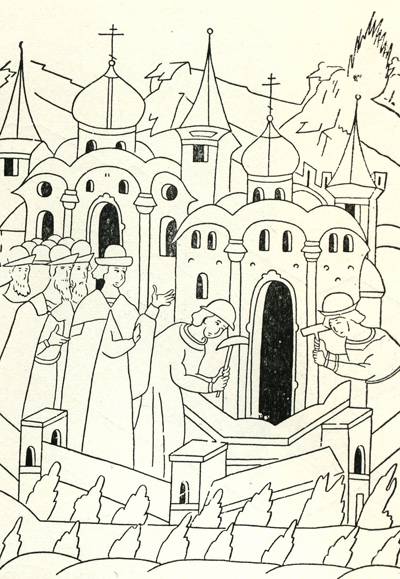

Preserved northern extensions to the

Fig.

65. The construction of temples in Bogolyubovo. Miniature

of “Litsevoj” Chronicle of XVI century.

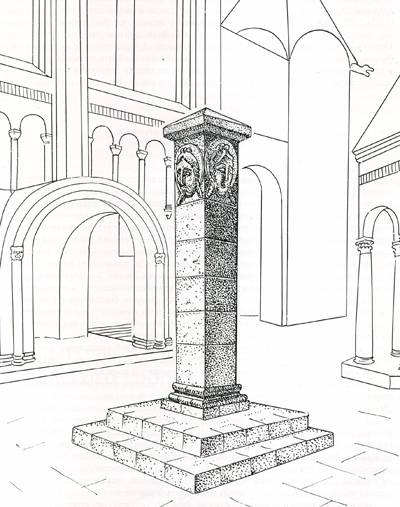

The area in front of the gate to the prince's

"burg" was beautified, paved with stone slabs with gutters-drains,

the 8-pillared dome over a chalice, opened by N.N. Voronin, was located

there41 (see Fig. 63).

The origin of the so-called “four faces” capital,

located in Bogolyubovo exhibition of Vladimir-Suzdal Museum-Reserve42

(Fig. 66), interested researchers for long time. A.I. Nekrasov believed that

the capital belonged to the "main pillar" of a princely palace43.

N.N. Voronin attributed it to one of the pillars of the hypothetical

opened western forechurch-baldachin of the

Fig.

66. So-called “four faces” capital. Modern view.

Fig.

67. “Our Lady’s Pillar” in XII century. Reconstruction by G.K. Vagner.

The author of this study considers the position of

G.K. Vagner as the most reasonable from the historical point of view (the

researcher provided several examples of the installation of such pillars in

The only caveat that we can do – that the stone block

with faces of the Virgin in XII century could stand not on a pillar, but on a

lower pedestal, so that believers could kiss it. This explains the poor

preservation of faces, made of high quality stone that could effectively resist

the "normal" weathering. In XIX century the block was laid in the

wall and could be kissed only from one side48, and since all four

faces survived poorly, for several previous centuries the block was to be

"kissed" from all sides.

We can date the "burg" of Andrey Bogolyubsky

only very tentatively. As it follows from the message of “Brief Vladimir

Chronicle”, quoted in Section 1, the prince's palace was built shortly after

the arrival of Andrey to Suzdal from

The question, when the "burg" disappeared

from the face of the earth, requires separate consideration. The stratigraphy

of the excavations of N.N. Voronin to the north of the preserved

stair-tower showed that after the thin cultural layer with ceramics of XIII

century the layers of XVIII-XIX centuries immediately follow49. This

researcher concluded that “a disaster befell the palace after a short time

after its construction”, and thought that the palace could be destroyed either

during the uprising of 1174, when the townspeople looted the prince's court,

either during the campaign of Gleb of Ryazan in 1177, or during the

Mongol-Tatar invasion50.

But these uprisings and gains could hardly so fatally

affect the destiny of a large white stone "burg", which was actually

a strong fortress: first, it was impossible to destroy (or burn) it completely

during an assault, briefly seizing or rebellion, and secondly, it could not

worn out and completely disappear within seventy years even in the conditions

of complete desolation (which, as we have shown in Section 1, did not take

place in pre-Mongol Bogolyubovo).

In XII-XIII centuries the "burg" of Andrey

Bogolyubsky could only be purposefully dismantled ("razed"), and that

would have required enormous labor and time costs. That could happen neither in

1174, neither in 1177, nor even in 1237-1238: we do not know precedents of

complete "razing" of Russian fortresses by the Mongols. In addition,

in the time of Batu a monastery had already been settled in Bogolyubovo

"burg"51, and exceptional religious tolerance of the

Mongols is well known.

Most likely, that the excavations of N.N. Voronin

to the north of the stair-tower were at he place of some buildings of the

"burg". In XIII century this place could be open (so the cultural

layer included ceramics), and in post-Mongolian time it could built up. In this

regard the cultural layer of XIII century at that site was so thin, and the

layers of XIV-XVII centuries were not found.

Thus, it is likely that non-survived buildings of the

"burg" of Andrey Bogolyubsky had the same fate as many pre-Mongolian

white stone buildings: they dilapidated gradually, deteriorated, were used for

building materials, and disappeared not later than the second third of the

XVIII century (when the southern extensions to Nativity church disappeared).

3.

The church52 of Nativity of the Virgin in

Bogolyubovo, apparently, was the central, highest and most richly decorated white

stone construction of the Prince’s "burg". The temple was built of

white stone of higher quality than other buildings of the “burg”.

Considering the question of dating of the temple, let

us recall once more the messages listed in Section 1. “Brief Vladimir

Chronicler” says: “And then Andrey Yurievich came from

The fact that the arch with the passage was "attached"

to the northern wall of the church and covered the arcature-columnar zone (see

Section 2 and Fig. 61), also shows that the

This position is confirmed by another chronicle

message – of Vladimir Chronicler (XVI century), to which the attention of the

author was attracted by T.P. Timofeeva56. Under 1158 it states:

"This Prince Andrey Bogolyubsky built the ramparts of the city, and

erected the stone Church of Nativity of the Holy Virgin on the Klyazma river,

and another church of Intercession of the Holy Virgin on the Nerl, and founded

the monastery”57.

And taking into consideration that, as we have shown

in Chapter 4, the term “to erect” usually meant in chronicles the construction

within one year, and many temples were really built within one construction

season, we must accept 1158 as the date of the Churches of Nativity and

Intercession (see Chapter 8).

In the end of XVII century the choir was broken and the

windows were widened in the

The western part of the northern wall, which bordered

with the arch and passage, survived above the choir, though it was turned from

the interior at the rebuilding62. The fact of masonry turning is

proved by the presence of blocks with "upside" notches for plaster;

blocks without notches (respectively, re-treated, inverted or displaced); small-sized

inserts in masonry; unevenly placed blocks (Fig. 68). The remaining walls are

preserved at 2-3 rows of masonry.

Fig.

68. Detail of the western part of the northern wall of the

Thus, the plan of the

Fig.

69. Plan of the

The lisenes of the temple had half-columns in the

middle and quarter-columns at the sides, the corner lisenes were united by the

corner three-quarter columns, the apses had thin half-columns (four on the

middle apse and two – on the side). The socle of the temple was decorated by

Attic profile. The bases of the half- and quarter-columns were also decorated

by Attic profile and had angular "claws". Let us note that we see the

similar "claws" in many Romanesque and Gothic churches of

The question of the number of heads of the temple is

easily solved – it was single-headed, as it was depicted at the XVII century

icon of Our Lady of Bogolyubovo (Fig. 58), and the

Temple had a choir (where the guests of Andrey

Bogolyubsky, not belonging to the Orthodox church, were to be led "to see

true Christianity and be baptized"65). The northern entrance to

the choir from the passage above the gate survived the rebuilding, the

threshold of current pass lies at the height of

But the

Fig.

70. The initial view of the

We must fully support the position of

N.N. Voronin that the choir of the

The fact that

in Assumption Cathedral in Vladimir, the Church of Intercession on the Nerl and

St. Demetrius Cathedral the choirs are located in the middle of the pillars, in

any case is not common and mandatory system for all pre-Mongolian temples of

North-Eastern Russia (for example, in Holy Transfiguration Cathedral in

Pereslavl-Zalessky and the Church of Boris and Gleb in Kideksha the choirs are

approximately at three-fifths of the height of the pillars). In the temples of

other ancient kingdoms (

Thus, we accept the reconstruction the

To answer this question, we can hypothesize that the

doorway between the passage and the choir in its present form is not a door, but

a window. Originally there was a "full-fledged" door at this place,

and when at the end of XVII century the choir was broken, this doorway, which

led “nowhere”, was turned to the window by the putting of two or three rows of

stone on its bottom. Perhaps the transformation of the door to the window was

caused by the turning of the interior masonry of the northern wall of the

Of course, it is only a hypothesis, which may be

confirmed or denied by a probe of the bottom of the existing doorway, which is

covered by a thick layer of plaster. But according to this hypothesis, we can

reconstruct the choir of the

However, as we have shown above, the location of the

choir at two thirds of the height of the pillars (by N.N. Voronin, see

Fig. 70) is also absolutely normal, moreover – the high choir enhances the

feeling of the height of the interior and emphasizes its solemnity (low choir,

on the contrary, creates the feeling of "cramped" interior and

"press" the people inside a temple).

Judging by archaeological discoveries in Bogolyubovo

(carved female and lion masks, head of the beast of the white stone water-jet)

we have all reason to consider after N.N. Voronin67 that the

temple had the same system of zooantropomorphous sculptural decoration, which

is present on the

The temple had perspective portals. Their columns were

smooth, and archivolts were probably carved69.

Let us consider the question of the forechurches of

the

The “Story of the death of Andrey” tells that the

Prince's body was put in a forechurch70. But extensive

archaeological researches found no remnants of forechurches71. In

this regard, E.E. Golubinsky assumed that the western forechurch was an

open porch72, D.I. Ilovaisky – that the church had an open

"portico"73, N.N. Voronin – that the western

forechurch could be “baldachin”, open from 3 sides, relying by its arches on

the temple wall and two pillars74. However, all these assumptions

were very arbitrary, and even N.N. Voronin, putting forward his version of

the type and location of the forechurch, found impossible to reflect it on his

reconstructions of the temple (see Fig. 63 and 70).

We are going to put forward our own version, what

forechurch “Story of the death of Andrey” tells about.

First, the putting of a dead body of the Prince in the

open vestibule (albeit under the "baldachin") was almost tantamount

to its abandonment in the street, but the logic of the “Story” says that the

body was put into some room, where two days later Abbot Arseny saw it and

insisted on the funeral service75.

Secondly, an open white stone forechurch (even in the

form of a "baldachine") was to have some foundations under the

pillars, and since very detailed excavations did not discover them, it is

likely that they never existed.

Third, we, following G.K. Vagner, have identified

more likely and logical place for the “four faces” capital, which

N.N. Voronin referred to a hypothetical open forechurch (see Section 2).

In this regard, we suggest the following: the temple

had closed forechurches, built not of white stone, but of wood (archaeological

researches are virtually unable to detect the remnants of wooden forechurches

in such a complex stratigraphy).

Between

the building of the church and the palace (late 1150s-early 1160s) and the

murder of Bogolyubsky (1174) about fifteen years passed, and it is not

surprising that the white stone "burg" in prosperity Suzdal Grand

Duchy in Andrey’s times (i.e. being completely safe from attacks of external

enemies) was gradually "overgrowing" by a set of wooden utilitarian

extensions (which, as a rule, forechurches for temples are). This situation is absolutely typical for Ancient

Russia.

Theoretically, such

wooden forechurches might have been available from the west, south and north of

the

In conclusion, let us remember the words of the

Chronicle: "This good-believing and Christ-loving Prince Andrew was like

the king Solomon, when erected a house of God and the glory stone

© Sergey Zagraevsky

Chapter

1.Organization of production and processing of white stone in ancient Russia

Chapter 2. The

beginning of “Russian Romanesque”: Jury Dolgoruky or Andrey Bogolyubsky?

in Suzdal in

1148 and the original view of Suzdal temple of 1222–1225

Chapter 4.

Questions of date and status of Boris and Gleb Church in Kideksha

Chapter 5.

Questions of architectural history and reconstruction of Andrey Bogolyubsky’s

Assumption

Cathedral in Vladimir

Chapter 6.

Redetermination of the reconstruction of Golden Gate in Vladimir

Chapter 7.

Architectural ensemble in Bogolyubovo: questions of history and reconstruction

Chapter 9.

Questions of the rebuilding of Assumption Cathedral in Vladimir by Vsevolod the

Big Nest

Chapter 10.

Questions of the original view and date of Dmitrievsky Cathedral in Vladimir

To the page “Scientific works”